Katherine May’s thought provoking book about taking a break, a sabbatical, a pause in life. It is a book about depression and anxiety but it is also a book about hope. It is a book about new beginnings.

There are gaps in the mesh of the everyday world, and sometimes they open up and you fall through them into somewhere else. Somewhere Else runs at a different pace to the here and now, where everyone else carries on. Somewhere Else is where ghosts live, concealed from view and only glimpsed by people in the real world. Somewhere Else exists at a delay, so that you can’t quite keep pace. Perhaps I was already teetering on the brink of Somewhere Else anyway; but now I fell through, as simply and discreetly as dust sifting between the floorboards. I was surprised to find that I felt at home there.

Everybody winters at one time or another; some winter over and over again.

Wintering brings about some of the most profound and insightful moments of our human experience, and wisdom resides in those who have wintered.

Winter is not the death of the life cycle, but its crucible.

Doing those deeply unfashionable things—slowing down, letting your spare time expand, getting enough sleep, resting—is a radical act now, but it is essential. This is a crossroads we all know, a moment when you need to shed a skin. If you do, you’ll expose all those painful nerve endings and feel so raw that you’ll need to take care of yourself for a while. If you don’t, then that skin will harden around you. It’s one of the most important choices you’ll ever make.

The problem with “everything” is that it ends up looking an awful lot like nothing: just one long haze of frantic activity, with all the meaning sheared away.

I had no idea how much these quiet pleasures had retreated from my life while I was rushing around, and now I’m inviting them back in.

That’s what humans do: we make and remake our stories, abandoning the ones that no longer fit and trying on new ones for size.

I’m tired, inevitably. But it’s more than that. I’m hollowed out. I’m tetchy and irritable, constantly feeling like prey, believing that everything is urgent and that I can never do enough.

Anxiety lurked in my body like groundwater, and every now and then it would rain and the level would rise up into my throat, surging into my sinuses, banking up behind my eyes.

All this time is an unfathomable luxury, and I’m struck by the uncomfortable feeling that I’m enjoying it a little too much.

I’m feeling the full force of the guilt of being unable to keep up, of having now fallen so far behind that I can’t imagine a way back in.

How could I ever admit that I chose the muffled roar of starlings over the noisy demands of the workplace?

I notice that a few are carrying their mobile phones in empty plastic glasses to keep them dry, as if they can’t be separated from them for even this long. I’m not the only one who has forgotten how to rest.

I had been wound so tight with stress that I could no longer see past my own knots, and now, having relaxed ever so slightly, I’m feeling the full force of its impact.

Nobody else seems to enjoy the cold or the bluster as I do. Winter is the best season for walking, as long as you can withstand a little earache and are immune to mud. Best are the coldest days when even that freezes solid and the ground crunches underfoot, firm and satisfying. A good frost picks out every blade of grass, the crenellated edge of every leaf. The cold renders everything exquisite.

Cailleach offers us a cyclical metaphor for life, one in which the energies of spring arrive again and again, nurtured by the deep retreat of winter. We are no longer accustomed to thinking in this way. Instead we are in the habit of imagining our lives to be linear, a long march from birth to death in which we mass our powers, only to surrender them again, all the while slowly losing our youthful beauty. This is a brutal untruth. Life meanders like a path through the woods.

But in recent weeks, my happy hibernation has been disrupted. I’ve come to call it the “terrible threes”: the dark insomniac hours when my mind declares itself, fully fired, in the middle of the night. It always happens at three a.m.: a long way past late, but too early to surrender and start the day. There, in the truest night, I lie in the dark and catastrophize. The night inches on. I could make a career out of worrying, if only anyone would pay me. What do I worry about during these long nights? Money. Death. Failure.

Yet here I am, edging even closer to the abyss, throwing away the secure underpinnings of my life by leaving my secure job. In daylight, I can make an account of the stress that made the decision to leave a sensible one—the slow encroachment that ate into my family life. But that’s in the daytime, when I value such things as calm and freedom. In the dark, I am struck by a dyspeptic bout of conservatism.

Now that I’m upright, my thoughts settle like flakes in a snow globe. Everything falls back into perspective. Once I abandon the fight to return to sleep and claim my wakefulness, I can find a slanting love for this part of the night, the almost-morning.

They say that we should dance like no one is watching. I think that applies to reading, too.

Sometimes writing is a race against your own mind, as your hand labors to keep up with the tide of your thoughts.

In At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past, the historian A. Roger Ekirch asserts that before the Industrial Revolution, it was normal to divide the night into two periods of sleep: the “first sleep,” or “dead sleep,” lasting from the evening until the early hours of the morning; and the “second” or “morning” sleep, which took the slumberer safely to daybreak. In between, there was an hour or more of wakefulness known as the “watch,” in which “Families rose to urinate, smoke tobacco, and even visit close neighbors. Many others made love, prayed, and . . . reflected on their dreams, a significant source of solace and self-awareness.” A study by Thomas Wehr and his colleagues attempted to replicate the conditions of winter sleep in prehistoric times, depriving subjects of artificial light for fourteen hours each night and observing what happened to their sleep patterns. After several weeks, the participants fell into a pattern of lying awake in bed for two hours before falling asleep for around four hours. They would then wake up and enjoy two or three hours of time characterized as contemplative and restful, and then take another four hours of sleep until morning. Most interesting of all, Wehr observed that the midnight watch was far from an anxious time for his subjects. They felt calm and reflective in these moments, and blood tests revealed elevated levels of prolactin, the hormone that stimulates the production of breast milk in nursing mothers. In most men and women, prolactin levels tend to be low, but the watch seemed to have “an endocrinology all of its own,” which Wehr compared to an altered state of consciousness similar to meditation.

My own midnight terrors vanish when I turn insomnia into a watch: a claimed sacred space in which I have nothing to do but contemplate.

A lifting of the obligation to endlessly do.

Have we really got so far into the realm of electric light and central heating that the rhythm of the year is irrelevant to us, and we no longer even want to notice the point at which the nights start getting shorter again?

We didn’t so much retreat from the world as let it recede from us.

When everything is broken, everything is also up for grabs.

Here is another truth about wintering: you’ll find wisdom in your winter, and once it’s over, it’s your responsibility to pass it on. And in return, it’s our responsibility to listen to those who have wintered before us.

D. H. Lawrence: “We must get back into relation: vivid and nourishing relation to the cosmos and the universe . . . We must once more practice the ritual of dawn and noon and sunset, the ritual of kindling fire and pouring water, the ritual of the first breath and the last.”

I used to think that these were wasted days, but I now realize that’s the point.

I am not being lazy. I’m not slacking. I’m just letting my attention shift for a while, away from the direct ambitions of the rest of my year. It’s like revving my engines.

But the politics of New Year seem excessively complicated to me. Even at the ripe old age of forty-one, I’m shy about asking if anyone’s free, lest I make myself look unpopular. Then, every year without fail, I discover the next day that many of my favorite people were sitting at home, bored, ruminating over the same dark thoughts that I was: “I bet everyone else is out there having fun. Why wasn’t I invited?“

We had barely finished our meal when we were called onto the deck because the skipper thought he’d seen something, and as we watched, a wisp of greenish smoke appeared overhead, almost close enough to touch. Untutored, I would have assumed it was a stray emission from one of the surrounding boats, but this apparently was the aurora: pale, evanescent, but tangible in a way that I hadn’t expected. It wasn’t an image flashed across the sky; it was an object in three dimensions, drifting slowly above our boat. At that moment, I realized that every image of the lights I had ever seen had been misleading. I had been poring over photographs of neon displays as lurid as disco lights and watching YouTube videos of lights that struck out against the night sky, bold and distinct. These are invariably sped up, the luminous greens and pinks enhanced by long exposures. Look closely, and you will see the stars shining through the aurora in every picture; the northern lights are not even bright enough to eclipse tiny pinpoints of light from trillions of miles away. They move slowly, like drifting clouds. Seeing them is an uncertain experience, almost an act of faith. You have to get your eye in, and I honestly don’t think I would ever have spotted them at all had I not been told they were there. I spotted the faint glow of the aurora above the harbor and supposed it might have been there all along. Just waiting for me to learn how to see it.

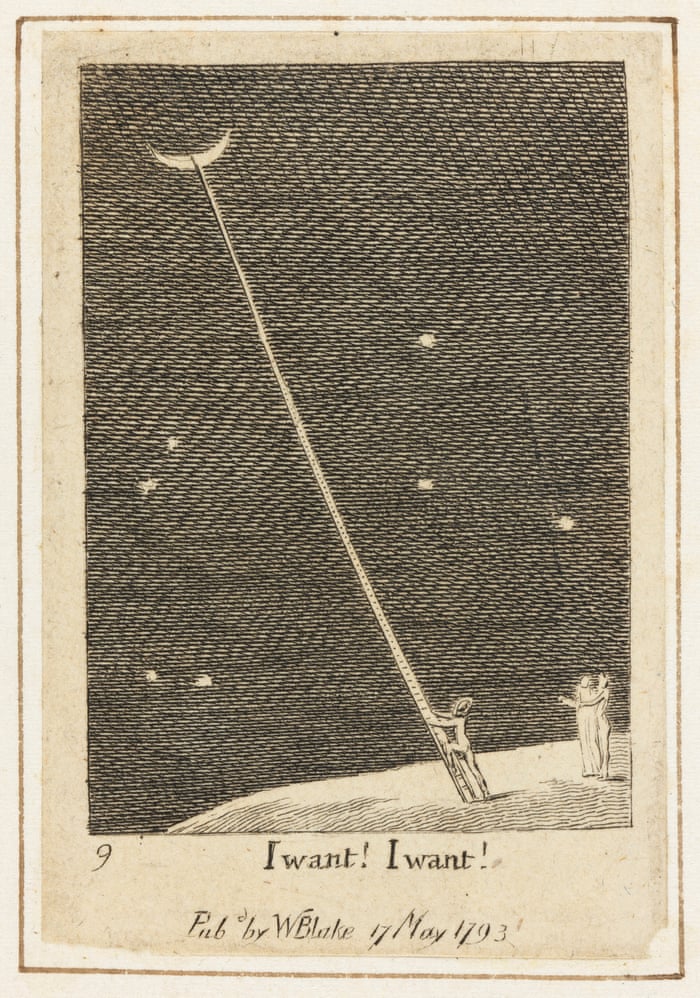

An etching by William Blake of a little man who’s propped a spindly ladder up against the moon. He’s just mounted the bottom rung, a long, impossible climb ahead. A caption reads, I want! I want! In the depths of our winters, we are all wolfish. We want in the archaic sense of the word, as if we are lacking something and need to absorb it in order to be whole again. These wants are often astonishingly inaccurate: drugs and alcohol, which poison instead of reintegrate; relationships with people who do not make us feel safe or loved; objects that we do not need, cannot afford, which hang around our necks like albatrosses of debt long after the yearning for them has passed. Underneath this chaos and clutter lies a longing for more elemental things—love, beauty, comfort…

‘You need to live a life that you can cope with, not the one that other people want. Start saying no.

All I can do is walk. I have nothing else.

The only thing breaking me was pretending to be like everyone else.

“I now think of it as mental influenza,” she says. “I don’t power on through, I don’t put up a façade, and I don’t keep it in. I take a couple of days off and look after myself until I’m well again. This has been a long journey for me, and swimming is just one of the changes I’ve made. I’ve cut out sugar, I make sure I get plenty of alone time, I go on long walks, and I’ve stopped saying yes to everybody. I’ve cut down my working hours. All of these things make a buffer, and I say I like to keep my buffer broad. Sometimes problems come up that narrow my buffer, and then I have to make sure I build it up again. Keeping well is almost a full-time job. But I have a wonderful life.”

The truth is that we all have ant years and grasshopper years.

Let us not aspire to be like ants and bees. We can draw enough wonder from their intricate systems of survival without modelling ourselves on them wholesale. Humans are not eusocial—we are not nameless units in a superorganism or mere cells that are expendable when we have reached the end of our useful lives. The life of a sociable insect has nothing to say about us. Our lives take different shapes. We do not work in a linear progression through fixed roles like the honeybee. We are not consistently useful to the world at large.

Usefulness is a useless concept when it comes to humans.

Alan Watts: “To hold your breath is to lose your breath.”

Life is, by its very nature, uncontrollable. That we should stop trying to finalize our comfort and security, and instead find a radical acceptance of the endless, unpredictable change that is the very essence of this life.

I’ve noticed lately a glut of posts on Facebook offering unsolicited advice on how to cope with a crisis: Hang on in there! they say, apropos of nothing. You are stronger than you know. They are presented like greetings cards, pastel text on dreamy backgrounds, the words rendered in elegant cursive as though scrawled by a particularly inspirational friend. Reading them, I always assume that they’re aimed at someone in particular, that the person who posted them has noticed some hint of distress and is sending out an oblique message of support. Either that or they are a cry for help, signals pitched into the ether to come back to their originators. This is where we are now, endlessly cheerleading ourselves into positivity while erasing the dirty underside of real life. I always read brutality in those messages: they offer next to nothing. There are days when I can say with great certainty that I am not strong enough to manage. And what if I can’t hang on in there? What then? These people might as well be leaning into my face, shouting, Cope! Cope! Cope! while spraying perfume into the air to make it all seem nice. The subtext of these messages is clear: Misery is not an option. We must carry on looking jolly for the sake of the crowd. While we may no longer see depression as a failure, we expect you to spin it into something meaningful pretty quick. And if you can’t pull that off, then you’d better disappear from view for a while. You’re dragging down the vibe. This is the opposite of caring. I’ve never believed—as others do—that social media is a place entirely constructed of fake lives and fake friendships, but I do think it’s another place to beware. There’s a collector’s mentality online; our social worth is given a single blunt number. We have to make sure that we’re not fooled by it. We have to make the same assessments that we always did about the quality of those connections, their individual meanings to us and the nurture that they can realistically offer us. Just as with the physical world, many of these friends will melt away at the first sign of trouble. The only difference is that the numbers are bigger online, and our missed connections feel more visible.

I’m beginning to think that unhappiness is one of the simple things in life: a pure, basic emotion to be respected, if not savored. I would never dream of suggesting that we should wallow in misery or shrink from doing everything we can to alleviate it, but I do think it’s instructive. After all, unhappiness has a function: it tells us that something is going wrong. If we don’t allow ourselves the fundamental honesty of our own sadness, then we miss an important cue to adapt. We seem to be living in an age when we’re bombarded with entreaties to be happy, but we’re suffering from an avalanche of depression. We’re urged to stop sweating the small stuff, yet we’re chronically anxious. I often wonder if these are just normal feelings that become monstrous when they’re denied. A great deal of life will always suck. There will be moments when we’re riding high and moments when we can’t bear to get out of bed. Both are normal. Both in fact require a little perspective. Sometimes the best response to our howls of anguish is the honest one. We need friends who wince along with our pain, who tolerate our gloom, and who allow us to be weak for a while when we’re finding our feet again. We need people who acknowledge that we can’t always hang on. That sometimes everything breaks. Short of that, we need to perform those functions for ourselves: to give ourselves a break when we need it and to be kind. To find our own grit, in our own time.

When I started feeling the drag of winter, I began to treat myself like a favored child: with kindness and love. I assumed my needs were reasonable and that my feelings were signals of something important. I kept myself well fed and made sure I was getting enough sleep. I took myself for walks in the fresh air and spent time doing things that soothed me. I asked myself: What is this winter all about? I asked myself: What change is coming?

I had walked away from something that in retrospect was toxic to me.