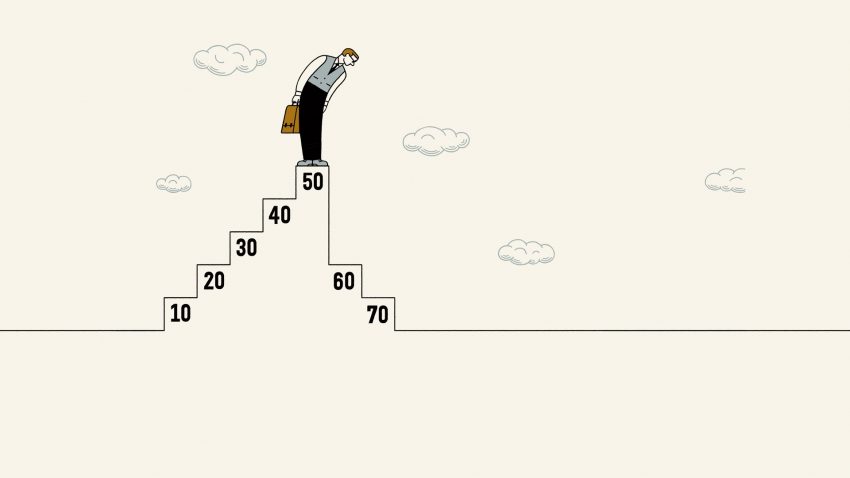

This was a good book to read before my 49th birthday! Arthur Brooks makes the case that after our mid thirties, we have to make the jump between fluid and crystallized intelligence if we are to continue contributing to society. Rigidly holding on to the “first curve” is often responsible for the “midlife crisis”.

He also highlights the difference between how Eastern and Western philosophies view the growth of the human being. The Eastern philosophies think of the human as a block of jade, and as you mature you chip away all that is inessential. The Western philosophies on the other hand think of life as a blank canvas that you have to keep adding on to to make it richer. Hence the “bucket list” being popular in Western cultures.

/media/img/posts/2019/06/WEL_Brooks_Spot4/original.png)

Here are a few more quotes from the book that caught my attention:

Was there any way to get off the hamster wheel of success and accept inevitable professional decline with grace? Maybe even turn it into opportunity?

What I found was a hidden source of anguish that wasn’t just widespread but nearly universal among people who have done well in their careers. I came to call this the “striver’s curse”: people who strive to be excellent at what they do often wind up finding their inevitable decline terrifying, their successes increasingly unsatisfying, and their relationships lacking.

You know intellectually that you can’t keep this party going forever, and you might even already see the signs that it is coming to an end. Unfortunately, you never gave much thought to the party’s end, so you only really have one strategy: Try to keep it going. Deny change and work harder. “Stein’s law,” named after the famous economist Herbert Stein from the 1970s: “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” Obvious, right? Well, when it comes to their own lives, people ignore it all the time.

Perfectionism and the fear of failure go hand in hand: they lead you to believe that success isn’t about doing something good but about not doing something bad.

Social comparison the “thief of joy.” – spend a few hours browsing Instagram and see how bad you feel about yourself. This is because you are comparing your success with your perception of others’ success,

A lot of things in your life were there really only to build up your image—to yourself and others—to signify that you were successful and special. Some of these things are physical trophies, “positional goods” that show you are a big deal to the world. These can be houses and cars and boats, of course. But don’t flatter yourself if these aren’t important to you (they aren’t to me), or if your success isn’t the kind that gives you a lot of money. Your trophies might well be social media followers, or famous friends, or living in a cool place by the world’s standards.

The point is that the symbols of your specialness have encrusted you like a ton of barnacles. Not only are these things incapable of bringing you any real satisfaction; they’re making you too heavy to jump to your next curve. You need to chip a bunch of them away.

In the desire for wealth and for whatsoever temporal goods . . . when we already possess them, we despise them, and seek others. . . . The reason of this is that we realize more their insufficiency when we possess them: and this very fact shows that they are imperfect, and the sovereign good does not consist therein.

That release from suffering comes not from renunciation of the things of the world, but from release from attachment to those things. A Middle Way shunned both ascetic extremism and sensuous indulgence, because both are attachments and thus lead to dissatisfaction. At the moment of this realization, Siddhartha became the Buddha.

We know more or less how to meet our desire for satisfaction but are terrible at making it last.

When it comes to success, you can’t ever get enough. If you base your sense of self-worth on success, you tend to go from victory to victory to avoid feeling awful. That is pure homeostasis at work. You need constant success hits just not to feel like a failure. That’s what we social scientists refer to as the “hedonic treadmill.” You run and run but make no real progress toward your goal—you simply avoid being thrown off the back from stopping or slowing down. The carrot dangled in front of you is the fleeting feeling that you’ve made it, despite the fact that you are emotionally running in place on the hedonic treadmill. And it is that much worse when your abilities are starting to decline—the carrot is gradually getting further away, despite the fact that you are running faster than ever. Thus, the dissatisfaction problem compounds the decline problem.

…Abd al-Rahman III, the emir and caliph of Córdoba in tenth- century Spain. Al-Rahman was an absolute ruler who lived in complete luxury. Here’s how he assessed his own life at about age seventy: I have now reigned above 50 years in victory or peace; beloved by my subjects, dreaded by my enemies, and respected by my allies. Riches and honors, power and pleasure, have waited on my call, nor does any earthly blessing appear to have been wanting to my felicity. Fame, riches, and pleasure beyond imagination. Sounds great, doesn’t it? But, as he goes on to write, I have diligently numbered the days of pure and genuine happiness which have fallen to my lot: They amount to 14.

To sum up, here are three formulas that explain both our impulses and the reason we can’t ever seem to achieve lasting satisfaction.

Satisfaction = Continually getting what you want

Success = Continually having more than others

Failure = Having less

Satisfaction = What you have (divided by) what you want.

Turning the treadmill off by managing our wants- manage the denominator.

“What is my why?” The bestselling author and speaker Simon Sinek always gives people in search of true success in work and life the advice that they need to find their why. That is, he tells them that to unlock their true potential and happiness, they need to articulate their deep purpose in life and shed the activities that are not in service of that purpose. Your why is the sculpture inside the block of jade. Most people spend their time on the what of their lives—they can’t see beyond the brushstrokes they’ve put on the canvas.

People don’t realize their unhealthy attachments in life until they suffer a loss or illness that makes the important things come into focus.

Post-traumatic growth. – cancer survivors tend to report higher happiness levels than demographically matched people who did not have cancer.

The secret to happiness is not the world’s glories, but rather to focus on the little contentments; to “cultivate our garden.”

Have you ever said, “My work is my life”? If you have, then your fear of decline is actually a type of fear of death. If you live to work—if your work is your life, or at least the source of your identity—proof of being fully alive is your professional ability and achievement. So when it declines, you are in the process of dying. As a striver, it was your force of will and indefatigable work ethic that got you to the top of your fluid intelligence curve—and profession—in the first place. Only when you face the truth of your professional decline—a kind of death—can you get on with your progress to the second curve. If you don’t, you will be like my friend, trying to fight the inevitable, or at least hoping that there is some way around it. And to face this truth means defeating the fear of your own demise—literal and professional. This fear handcuffs you to your fluid intelligence curve. If you can master it, the reward is incalculable: it will set you free.

“The idea of death, the fear of it, haunts the human animal like nothing else,” anthropologist Ernest Beckerwrote in his classic 1973 book, The Denial of Death.

Dying isn’t necessarily the inferior alternative. Jonathan Swift made this point in his 1726 novel Gulliver’s Travels. In the nation of Luggnagg, the hero, Gulliver, finds a small group of people, born at random, called “struldbrugs.” They look normal but are immortal. What luck! This is what Gulliver thinks until he learns that while they do not die, they do age and suffer the typical ailments of old people—the only difference being that the ailments are not lethal. They lose their eyesight and hearing and become senile but never die. At eighty, the government renders them legally dead and unable to own property or work. They live forever as unproductive wards of charity, horribly depressed and effectively invisible

Don’t be a “professional struldbrug” – ineffective and treated with a weird combination of pity and contempt by others.

“Achilles effect,” from Homer’s Iliad. He had to decide whether to fight in the Trojan War, promising certain physical death but a glorious legacy, or return to his home to live a long and happy life but die in obscurity.

Marcus Aurelius reminds us that our efforts at posterity always fail, and thus are not worth pursuing.

If you love your work so much, you might as well enjoy it while you are doing it. If you spend time thinking about and working on your legacy, you are already done.

In the words of sixteenth-century French essayist Michel de Montaigne, “To begin depriving death of its greatest advantage over us, let us deprive death of its strangeness, let us frequent it, let us get used to it; let us have nothing more often in mind than death.”

But exposure does more than just defeat fear. Contemplating death can even make life more meaningful. As the novelist E. M. Forster put it, “Death destroys a man: the idea of Death saves him.” Why? Simply put, scarcity makes everything dearer to us. Remembering that life won’t last forever makes us enjoy it all the more today. It is a great irony about succeeding in the modern world that those who specialize in dominating fear—who rise to any challenge, concede no weakness, and meet any foe—are often desperately afraid of decline. But within this very irony resides a magnificent opportunity to beat fear once and for all and thus truly to be the person you have made yourself out to be.

There is a famous Zen Buddhist story about a band of samurai who ride through the countryside causing destruction and terror. As they approach a monastery, all the monks scatter in fear, except for the abbot, a man who has completely mastered the fear of his own death. The samurai enter to find him sitting in the lotus position in perfect equanimity. Drawing his sword, the leader snarls, “Don’t you see that I am the sort of man who could run you through without batting an eye?” The master responds, “Don’t you see that I am a man who

could be run through without batting an eye?” The true master, when his or her prestige is threatened by age or circumstance, can say, “Don’t you see that I am a person who could be utterly forgotten without batting an eye?”

With decline, you don’t have to experience it alone. In fact, you shouldn’t. The problem is that many people do decline alone: on their way up they have let their relationships wither, so on the way down they don’t have a human safety net. This makes any change in the second half seem all the more difficult and risky.

“Happiness is love. Full stop.”

“There are two pillars of happiness. . . . One is love. The other is finding a way of coping with life that does not push love away.”

Paul Tillich put it like this in his classic book The Eternal Now: “Solitude expresses the glory of being alone, whereas loneliness expresses the pain of feeling alone.”

“The well-being benefits of marriage are much greater for those who also regard their spouse as their best friend.” Equally important, your marriage cannot be your only true friendship. Having at least two—meaning at least one not being the spouse—was associated with higher levels of life satisfaction, self-esteem, and lower levels of depression. It is a lot of pressure on a marriage to fill almost every emotional role and makes rough patches in a marriage all the more catastrophic and isolating. But having your spouse or partner as your one and only close friend is imprudent, like having a radically

undiversified investment portfolio.

Do you have real friends—or deal friends?

You seek the worldly rewards of success, you achieve some (or a lot) of them, and you may be deeply attachedmto these rewards. But you must be prepared to walk away from these achievements and rewards before you feel ready.

The Camino is all about walking, not arriving, which lays bare the satisfaction conundrum: Fulfillment cannot come when the present moment is little more than a struggle to bear in order to attain the future, because that future is destined to become nothing more than the struggle of a new present, and the glorious end state never arrives.

“It’s your road and yours alone,” wrote the Sufi poet Rumi. “Others may walk it with you, but no one can walk it for you.”

If you want to make a deep human connection with someone, your strengths and worldly successes won’t cut it. You need your weaknesses for that.

But you still do have to jump. And as people remind me all the time, that means definitively leaving what is known and comfortable, and striking out in a new direction in life.

Ocean fishing is fun but really different from fishing in a lake—you don’t just throw in your line and expect to catch something. I learned this the first time I tried, at about age eleven. For a couple of hours, I stood casting into the water off the rocks, without a single bite. After a while, along came a wizened old fisherman from the area, who asked me how it was going. “Lousy,” I told him. “Nothing’s biting.” “That’s because you’re doing it wrong,” he told me. “You have to wait for the falling tide—when the tide is going out fast.” It seems kind of counterintuitive, he explained, because you see the water rushing out and assume the fish would be going out to

sea as well. However, this is when the plankton and bait fish are all stirred up, making the game fish crazy and looking to bite everything. Together, we watched and waited for about forty-five minutes until the tide was moving out fast. At that point, the old man said, “Let’s fish!” We cast out and, sure enough, within seconds started pulling in fish, one after another. We did that for about half an hour—what fun! Afterward, relaxing on the rocks, the old man lit a cigarette and began to wax philosophical. “Kid, there’s only one mistake you can make during a falling tide,” he said. “What’s that?” I asked. “Not having your line in the water.” I have remembered that day many times while writing this book. There is a falling tide to life, the transition from fluid to crystallized intelligence. This is an intensely productive and fertile period. It is when you jump from one curve to the other; when you face your success addiction; when you chip away the inessential parts of life; when you ponder your death; when you build your relationships; when you start your vanaprastha. Unfortunately, the falling tide of your life is also incredibly scary and difficult—it may even feel like some sort of midlife crisis. It might feel like everything you’ve worked for is rushing away. Seeing it as tragedy can be easier than seeing it as opportunity.

Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark

For the straightforward pathway had been lost.

“Lifequake” – significant change in life occurs, on average, every eighteen months.

Nothing is more predictable than change.

“Man was made for conflict, not for rest,” Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote.

“In action is his power;

not in his goals

but in his transitions man is great.”

458 BC, Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus was the dictator of Rome when the city was under siege. He led Rome to victory, remained in power long enough to see a return of stability, and then abruptly resigned. He retired to his small farm, where he worked and lived humbly with his family. Had he remained a dictator in Rome after his victory, he would probably today be a historical footnote—a man who governed as a dictator for a few years, gradually became ineffective and unpopular, held on as long as possible, and was assassinated. We certainly

wouldn’t have named a city in Ohio after him. He is remembered as great because he wasn’t afraid to walk away.

We should seek work that is a balance of enjoyable and meaningful. At the nexus of enjoyable and meaningful is interesting.

In Tibetan Buddhism there is a concept called “bardo,” which is a state of existence between death and rebirth.

In The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, Buddhist monk Sogyal Rinpoche describes bardo as being “like a moment when you step toward the edge of a precipice.” You know you have to jump to be free, but it’s scary. But then you jump; there is a brief transition; you are born anew.

Use things. Love people.

The writer David Foster Wallace once said, astutely, “There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship.”