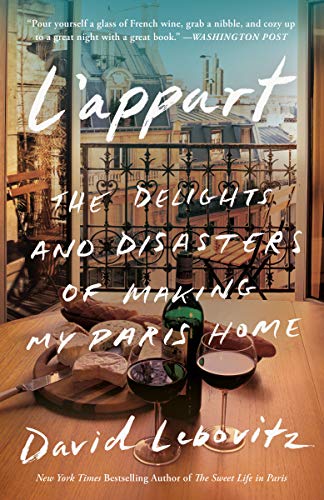

Tragicomic story about the famous food blogger remodeling his Paris apartment. On the surface it is a series of rants about the remodeling, but it delves into the psyche of the Parisian. It may help you navigate your life if one day you find yourself living long-term in Paris.

The part of being French that I’ve definitely mastered is that when it’s your turn, you don’t think about anyone behind you.

In America, your driver’s license or passport is the most important document in your life. In France, it’s the electric bill. Your facture d’électricité is the document that proves that you live in France.

The French don’t mind provoking others, which isn’t considered a fault, but part of the jeu (game) of everyday life.

A sticker you’ll sometimes see around the city reads: J’ rien. J’suis Parisien, “I love nothing. I am Parisian.”

Appearing enthusiastic can come off as unseemly, often construed as being très américain. If you do like something, it’s pas mal (not bad), which also works in the other direction: if you don’t like something, it’s pas terrible (not terrible).

I started and stopped my hunt for an apartment more times than a terrified American driver behind the wheel of a Citroën (who shall remain nameless) attempts to enter the chaos of traffic encircling the Arc de Triomphe, the famed (and feared) roundabout that caps off the Champs-Élysées where all bets are off, and so is your automobile insurance: Many policies have an exclusion if you drive there. I’ve stopped pushing my luck and avoid the traffic roundabouts in Paris, but Romain just steps on the gas and goes for it without a second thought.

When I moved to France, it was almost unheard of to have Internet access at home. “It will steal your soul!” people in Paris warned me.

The French proclivity for discretion, especially when it comes to discussing anything that has to do with money, extends to not being so gauche as to put a sign on your apartment window, which would let others know that you are willing to take something as distasteful as money for it. If you do see a “For Sale” sign, consider it an indication that the owners are having a hard time unloading the place.

The Left Bank is historically mesmerizing and sumptuous, but if you live on one side of Paris—say, on the Left or Right Bank—you rarely cross the river to visit the other side. Once you’re in a neighborhood, that’s where your life is. It helps to think of Paris as a collection of small villages bundled together, each one offering its own butchers, markets, bakeries, pharmacies, and even its own city hall. When you get to know everyone, you don’t want to leave.

I hoped to stay in the 11th arrondissement, one of the largest in Paris, spanning from Père Lachaise Cemetery to the Place de la République, as well as bordering the Marais. It’s considered hip, or bobo; les bobos are the upscale Parisian version of a hipster—although none are knitting bonnets, like they do on the subways in Brooklyn; or raising chickens in their henhouse, like they do in Oakland; or building smoking and curing sheds in their backyards, like they do in Portland. Their primary activities are smoking (not the kind that flavors artisanal bacon) and drinking beer, not making it. Still, it’s a very diverse neighborhood that has a lot going for it; it borders the multicultural Belleville quarter and is a short walk to the 10th arrondissement, where many of the best new chefs in Paris have opened their restaurants. And because the 11th is quite vast, parts of it are (or were) affordable because there are so many apartments there.

The single-digit arrondissements, including the Marais, are certainly more familiar to visitors, but are very, very expensive.

The double-digit arrondissements are more diverse, and each has a distinct feel. Being more working class, there’s a greater sense of community. Some are certainly less polished than the single-digit arrondissements, with narrow streets and passages instead of grand avenues, but they have a more neighborhood feel. And while the chicest chocolate and pastry shops are in the more upscale areas, young chefs and bakers have opened places in the outer arrondissements that are casually inventive, and less expensive.

Marché d’Aligre, which I think is the most exciting market in Paris.

(Looking at apartments in Paris, I quickly learned the transformative powers of a wide-angle lens.)

Spécial is one of those elusive French words that means something (or someone) is…peculiar. The use of it is one of the rare times that the French are noncommittal about their opinion. It’s a nebulous designation, so you need to decide for yourself if whatever pluses something has will outweigh the minuses. It’s usually not bad, but a warning that a heads-up is in order.

Parisians don’t habitually smile, and they especially never walk around grinning for no reason. People who walk around with smiles on their faces are either trying to pick someone up, or they’re American.

Another way to say “good luck” is to say “Merde!,” a custom that goes back to a time when the French took horse-drawn carriages to the theater. A sign that a show was a success was an abundance of horse merde piled up around the theater. (I assume dog doo didn’t count; otherwise, success would be harder to determine in Paris.)

As someone who is frugal, I’m jealous of how the French are intricately careful with their spending. Money is never handed over until it’s absolutely necessary. Americans are ready and willing when it’s time to pay; we’ve got our credit cards out of our wallets even before the cashier has finished ringing up our order.

Paris will constantly remind you who’s boss. But every once in a while, it throws you a bone.

Like Sicilians, who don’t have a verb tense to describe the future, the French aren’t so adept at imagining other possibilities. With soup plates that are only for soup and salad forks that can only be used for salads, the French get locked into how things should be, rather than seeing how they could be. That strategy is great for preserving the grandeur of the past, but hasn’t been as successful for envisioning beyond the present.

You never feel more American than when you leave America. But I’ve learned that nothing makes you feel more American than being faced with a European appliance.

“There is no dryer. People don’t have dryers in Paris. They use drying racks.”

Telling someone in France that they did something that was not correct is an affront to their honor, almost as severe as being told they’re mal élevé, or “badly raised.”

All that was left in the bathroom was a roll of toilet tissue sitting on the counter with the last of a few wayward sheets of paper trailing off the side, which had not been worth the previous owner’s effort to pack. (Although I’m sure it was a tough decision to leave it behind.)

Everything is negotiable in France, which means everything has value. But in France, the currency that has the most value is information. Getting it is a delicate skill because it’s not always easy to obtain.

The lawyer friend in Paris who helped me navigate through the thorny issues that came up when I was purchasing the apartment made sure I understood that after I closed, “the worst thing you can do is let your neighbors know they have any power over you. Once they do, it’s all over.”

The closing line that ends nearly every formal French correspondence: “Je vous prie d’agréer l’expression de mes salutations distinguées”…“I pray that you accept my distinguished regards.”

If you are willing to pay for it, the service and quality in France is second to none.

“We had a revolution, but we didn’t kill the king.” And even today, French society remains highly structured and layered. A common person doesn’t rise through the ranks to become prime minister or président. Those positions are filled by those who are carefully groomed at special schools for the elite to become professional politicians, and you don’t hear politicians talking about their humble beginnings, working as a dishwasher in a restaurant after school or delivering newspapers on their bikes.

Like the doors of French kitchens that separated les domestiques from the well-heeled, the politesse inherent in the French language also keeps others at a distance. Unlike English, French has a familiar and a formal verb tense. If you are friendly or close to someone, you tutoyer them. When speaking to someone you don’t know, or someone whom it’s prudent to keep a polite distance from, you vouvoyer them.

Thankfully, the French are forgiving of foreigners who mangle their beautiful language, because they know it’s a challenge, even for them.

The color has become such a fixture in France that it’s just a matter of time before the French rugby team, known as les Bleus, becomes les Aubergines.

Everybody knows the perfect time and place to hatch rational ideas is online at 2:45 A.M.

At any given time, there are nearly 26 million items for sale on the site. LeBonCoin.fr is less polished than eBay. Sellers have no problem putting their phone numbers on the site because of the French preference for the process over the result. Why send an e-mail, which takes eight seconds, when you can have a leisurely thirty-minute phone chat with a stranger about a busted garden gnome they’re selling?

A phrase you hear a lot in France is en principe, or “in principle.” The fromagerie or bank is open on Thursdays, en principe…

The apartment was a disaster, a word that comes from the French des astres, or “from the stars.”

I admire that the French can be explosive one minute, then perfectly charming the next, as if nothing had ever happened.

Being confrontational is part of the French character. (Americans think we are, but for all our bravado, we’re not in the same league as the French.)

Finding things in this city can be like trying to catch a feather: the more desperately you search for something, the more elusive it becomes.

“You need to withhold payment as long as possible. No one in France would ever pay a bill until the last possible moment. Make them soif [thirsty] for it.”

Like the leftover croissants that are stuffed with almond paste and baked again and sold the next day, nothing is wasted in France.

In the far corner of the room was the chiottes, a word that the French use colloquially to describe a small bathroom. Trying to act more French, I was casually throwing that term around, including in conversations with the women at the plumbing showrooms—until I learned it translated to “shithouse.” I learned the power of keeping one’s mouth shut, and stopped using it.

Standing at around five feet tall, like most French people he packs a lot of personality into his compact size.

“Hangry” hadn’t made it into the franglais lexicon, perhaps because the “h” isn’t pronounced in French, and angry is a natural state in France.

A few jaws would have dropped had they not been clamped around unlit cigarettes.

(French people love giving directions; it gives them a chance to tell someone else what to do.)

Being winter, it was la grippe season. During those months, I do whatever I can to avoid touching handrails and grabbing bars on the métro, since the idea of sneezing into your elbow hasn’t made it across the Atlantic yet.

Shaking hands is the way men in France traditionally greet each other, a holdover from the days when men carried weapons: it proved neither party was holding something dangerous. I now understand why they continue this tradition.

No one in France would dream of paying for anything until it was absolutely necessary, and certainly not without a lot of discussion and assurances being made before any payment changed hands.

Nearly a decade and a half of living in France had taught me to photocopy every piece of paper that crossed my path, no matter how insignificant it may seem at the time.

I’d learned that a healthy sense of humor is necessary to live in a foreign country, especially at some of the more perplexing things that happen.

I didn’t lèche-vitrine, or “lick the window,” the French phrase for window shopping.

The French can take a while to warm up to people they don’t know. But when they do, the friendship is genuine and sincere.

The French don’t mess around delivering bad news. That’s how it is. C’est comme ça.

I thought the project was finished. But it wasn’t done with me yet.

After two years of working on purchasing the apartment, then renovating it, in one evening I’d learned enough to realize that I’d made a huge mistake. I had been in over my head right from day one, not understanding the intricacies of purchasing an apartment in a foreign country, with all those new terms and concepts, and customs, to understand. I was sideswiped by a real estate agent, and tangled for months with a contractor on the renovations. I clearly had had no business moving to a foreign country, let alone buying an apartment in one. My head had been in the stars. And now everything had been ruined—all that I had invested in Paris, not just financially, but emotionally, was in this apartment, and it was a complete désastre.

I was happy to not have to contend with the “plaster of Paris”—the calcium in our water that grinds hot water heaters, coffee-makers, irons, and dishwashers to a halt. The only liquid I go through more bottles of than wine is white vinegar.

I looked at my checkbook, imagining writing another enormous check, and wondered if this was going to be my life in Paris from now on—problem after problème, check after chèque.

I ended up not leaving Paris, but it took me a few years to feel correct again. I was in over my head right from the start, and didn’t grasp the language or the culture enough to take on such a daunting project. But regardless of the cultural hurdles and differences, it wasn’t France, or the French, who were at fault. It was me. (I’m not French enough yet to deflect blame by pointing out I wasn’t responsible for being in a situation that I wasn’t ready to embark upon.)

The kaleidoscope of Paris had shifted for me. The elements were the same, but I moved them around and saw another side of the city.

Paris was always Paris, and the French were…well, the French. But because of what happened—j’avais mûri, I had “ripened,” as they say.

Living abroad, I learned and acclimated to different ways of doing things. Sometimes it’s learning not to touch the produce at the market. Other times, it’s going into a situation expecting the worst, instead of the best. In France, one uses système D, a way to démerder, or get out of the merde, by being resourceful and determined to get the job done, by whatever means you can.

I learned to adapt. I’m no longer surprised at people crumpling up papers and shoving them back in my mailbox, or at being sent home by a bureaucrat to get a piece of paper, which they’ll wave away when I wait in another long line to give it to them.

Flaws are part of life, and nothing is perfect, even if it appears that way from afar.