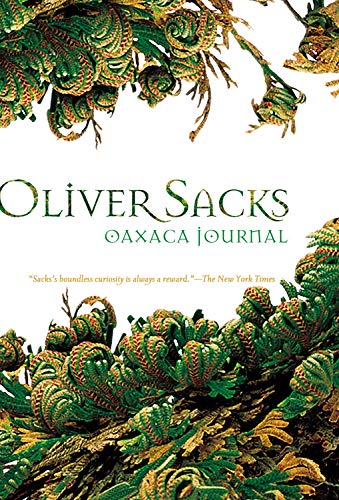

Supposedly a book about ferns, which it does a good job with. Delves into a brief history of Mesoamerica, specifically Oaxaca in typical Oliver Sacks fashion.

Amateurs—lovers, in the best sense of the word

Ferns had survived, with little change, for a third of a billion years. Other creatures, like dinosaurs, had come and gone, but ferns, seemingly so frail and vulnerable, had survived all the vicissitudes, all the extinctions the earth had known.

There is almost always this doubleness, that of the participant-observer, as if I were a sort of anthropologist of life, of terrestrial life, of the species Homo sapiens. (This, I suppose, is why I took Temple Grandin’s words as the title of An Anthropologist on Mars, for I, no less than Temple, am a sort of anthropologist, an “outsider,” too.) But is this not so of every writer as well?

Oaxaca has the richest fern population in Mexico

The extreme inequity of income, how Mexico has more billionaires than any other country save the U.S., but also more people living in desperate poverty.

I often have to go to professional meetings, meetings of neurologists or neuroscientists. But the feeling of this meeting was utterly different: There was a freedom, an ease and lack of competitiveness I had never seen in a professional meeting. Perhaps because of this ease and friendliness, the botanical passion and enthusiasm that everyone shared, perhaps because I felt no professional obligation resting on me, I began going to these meetings regularly, every month.

“The veriest greenhorn and the highest authority have always been on an equal footing as members

An old colonial capital surrounded by a modern city of 400,000 people or so.

Tobacco was nearly everywhere in the Americas, it is thought, by the time of Christ. An eleventh-century pottery vessel shows a Mayan man smoking a roll of tobacco leaves tied with a string—the Mayan term for smoking was sik’ar (to think that I have enjoyed cigars for years, and never realized the word was of Mayan origin!).

Visiting Cuba and seeing the natives smoking, another explorer, Rodrigo de Jerez, brought the custom back to Spain—when his neighbors saw smoke billowing from his nose and mouth, they were so alarmed they called in the Inquisition, and Jerez was imprisoned for seven years. By the time he got out of prison, smoking had become a Spanish craze.

There are huge, compacted towers of chilies, like bales, or castles—bright green, yellow, orange, scarlet, these seem very characteristic of Oaxaca. There are at least twenty types of chilies in common use—chile de agua, chile poblano, and chile serrano are the commonest fresh ones; there are also chile amarillo, chile ancho, chile de arbol, chile chipotle, chile costeno, chile guajillo, chile morita, chile mulato, chile pasilla de Oaxaca, chile piquín and a whole family of chilies going under the name of chilhuacle.

The Maya made a somewhat different version—their choco haa (bitter water) was a thick, cold, bitter liquid, for sugar was unknown to them—fortified with spices, corn meal, and sometimes chili. The Aztec, who called it cacahuatl, considered it to be the most nourishing and fortifying of drinks, one reserved for nobles and kings. They saw it as a food of the gods, and believed that the cacao tree originally grew only in Paradise, but was stolen and brought to mankind by their god Quetzalcoatl, who descended from heaven on a beam of the morning star, carrying a cacao tree. (In reality, Robbin says, it probably originated in the Amazon, like so many species; but we still remember this myth in the Latin name of the tree, Theobroma, “food of the gods.”)

But why, I wonder, should chocolate be so intensely and so universally desired? Why did it spread so rapidly over Europe, once the secret was out? Why is chocolate sold now on every street corner, included in army rations, taken to Antarctica and outer space? Why are there chocoholics in every culture? Is it the unique, special texture, the “mouth-feel” of chocolate, which melts at body temperature? Is it because of the mild stimulants, caffeine and theobromine, it contains? The cola nut and the guarana have more. Is it the phenylethylamine, mildly analeptic, euphoriant, supposedly aphrodisiac, which chocolate contains? Cheese and salami contain more of this. Is it because chocolate, with its anandamide, stimulates the brain’s cannabinoid receptors? Or is it perhaps something quite other, something as yet unknown, which could provide vital clues to new aspects of brain chemistry, to say nothing of the esthetics of taste?

Vegetables too are immensely varied, with more varieties of beans than I have ever imagined, bringing home to me that beans, along with corn, are still the basic Mesoamerican food, as they have been since the dawn of agriculture here eight thousand years ago. Rich in protein, with amino acids complementary to those of corn—the two of them, together, supply all the amino acids one needs. We see chunks of white, chalky limestone everywhere, used for grinding with the corn, which makes its amino acids more digestible.

Tomatoes and tomatillos, I reflect, like “Indian corn,” potatoes too, were also gifts of the New World to Europe.

This market is so rich, so various, that, reluctantly, I put my notebook away. It would need more talent, more energy than I have, to begin to do justice to the phantasmagoric scenes here.

I long for my camera, though photographing might be even more offensive (offense has been caused by outsiders, who will wander through the market buying nothing, but snapping whatever, whomever, they think cute or picturesque).

Several of us carry “the bible,” the Pteridophyte Flora of Oaxaca, Mexico.

We are now driving to the East Sierra Madre. I ask Scott about the many red flowers we pass. They are Solanum, he says. He tells me that some other species of Solanum are bat-dispersed and have greenish or white flowers, while these, bird-dispersed, have red flowers. The bat-dispersed ones waste no metabolic energy producing what would be, for them, a useless red pigment.

Certain kinds of red and orange fruit seem to have appeared only in the last thirty million years or so, in tandem with the evolution of trichromatic vision in monkeys and apes (though birds had developed trichromatic vision long before). Such fruits, a staple of many monkey diets, were particularly visible to trichromatic eyes in the tangled jungle foliage, and the plants, in turn, relied on the monkeys to disperse their seeds in their feces.

Long after the sexuality of flowering plants was recognized, the reproduction of ferns remained a mystery. It was believed, Robbin told me, that ferns had seeds—how else could they reproduce?—but since no one could see these, they assumed an odd and almost magical status. Invisible themselves, they were thought to confer invisibility on others: “We have receipt of fern-seed, we walk invisible,” says one of Falstaff’s henchmen in Henry IV.

in addition to the familiar fern plant with its spore-bearing fronds, the sporophyte, there also existed a tiny, heart-shaped plant, very easily overlooked, and that it was this, the gametophyte, which bore the actual sex organs. Thus there is an alternation of generations in ferns: Fern spores from the fronds, if they find a suitably moist and shaded habitat, develop into tiny gametophytes, and it is from these, when they are fertilized, that the new sporophyte, the baby sporeling, grows.

The Old World knew nothing like the powerful hallucinogenic drugs of Mexico—ololiuhqui (which the Spanish, when they encountered it, called semilla de la Virgen, seed of the Virgin); the sacred psilocybin mushroom, teonanacatl, God’s flesh (its active constituents also lysergic acid derivatives); and in the north of Mexico, overlapping the southern U.S., the buds of Lophophora williamsii, the peyotl cactus, sometimes called mescal buttons (though these have nothing to do with mescal, the distilled liquor made from the agave plant).

The more exotic South American hallucinogens, such as ayahuasca (the vine of the soul), made from the Amazonian vine Banisteriopsis caapí

The trypt-amine-rich snuffs—Virola, yopo, cojoba—the way in which their active ingredients are all so similar chemically, and so close in structure to serotonin, a neurotransmitter; and the way in which they were all discovered in prehistoric times (was it by accident, or trial and error?). We wonder why plants so different botanically should converge, so to speak, on such similar compounds, and what role such compounds play in the plant’s life—are they mere by-products of metabolism (like the indigo found in so many plants); are they used (like strychnine or other bitter alkaloids) to deter or poison predators; or do they play some essential roles in the plants themselves?

Oaxaca as a uniquely rich botanical borderland where plants of northern origin, like these pines, mingle with South American plants that have migrated north.

Animals, higher plants, even hornworts, he says, may think themselves superior, but ultimately we are all dependent on about a hundred species of bacteria, for only they know the secret of fixing the air’s nitrogen so that we can build our proteins.

Here in Mexico, Boone is saying, you have to use your brains to know what’s going on. In the States everything is published, organized, known. Here it is under the surface, the mind is challenged all the while.

The richness of Oaxaca’s ferns seems miraculous, for there are no more than a hundred or so in New England, perhaps four hundred species in the whole of North America. There are ferns in all latitudes—a brave thirty species in Greenland, for example—but far more as one goes toward the Equator. There are nearly 1,200 in Costa Rica, where Robbin teaches a course every year.

We are bathed in nitrogen, the atmosphere is four-fifths nitrogen. All of us, animals and plants and fungi alike, need it to manufacture nucleic and amino acids and peptides and proteins. But no organism other than bacteria can make use of it directly, so we are all dependent on these nitrogen-fixing bacteria to convert atmospheric nitrogen into forms of nitrogen the rest of us can use.

Intensive cultivation of a single crop tends to deplete the nitrogen in the soil quickly, but the Mesoamericans discovered early on, as other agricultural people did, by trial and error and experimentation, that beans or peas grown along with the corn could help replenish the soil more rapidly. (It was also discovered that alder trees, though not legumes, could similarly fertilize and enrich the soil, making possible a more intensive cultivation of other crops. The planting of alders had become an integral part of Mexican agriculture by 300 B.C.) In Europe, Robbin points out, many other legumes such as clover and alfalfa and lupin were grown as animal forage, and these were even more effective in restoring nitrogen to the soil than peas or beans. In China and Vietnam, he continues, warming to his theme, the great restorer is not a legume, not a flowering plant at all, but a tiny water fern, Azolla, which engulfs and lives with a nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium, Anabaena azollae. Rice, half-submerged in rice paddies, grows much more vigorously if Azolla is ground into the mud—in Vietnam, they call this green manure.

I am fond of bracken, or brake, I confess, partly because the old names excite me. There are fourteenth-century manuscripts that speak of “braken & erbes,” and the name survives in many Germanic languages, including Norwegian and Icelandic. It is a pleasure to look at, with its solitary spreading frond, light green in the spring, darkening later, sometimes covering sunny hillsides. If one is camping out, it is comfortable to sleep on, better than straw, because it absorbs and insulates so well. But it is one thing to sleep on it, admire it, and quite another to eat it, as cattle and horses sometimes do when the tender young shoots come up in spring. Animals that eat bracken may develop the “bracken-staggers,” because bracken contains an enzyme, thiaminase, which destroys the thiamine necessary for normal conduction in the nervous system. As a neurologist, this intrigues me, for such animals may lose their coordination and stagger, or show “nervousness” or tremor, and if they continue to eat the bracken, they will get convulsions and die. But this, I now find, is only a tiny part of bracken’s repertoire. Robbin calls bracken “the Lucrezia Borgia of the fern world,” for it packs a series of horrors for the insects that eat it. The young fronds release hydrogen cyanide as soon as the insect’s mandible tears into them, and if this does not kill or deter the bug, a much crueler poison lies in store. Brackens, more than any other plant, are loaded with hormones called ecdysones, and when these are ingested by insects, they cause uncontrollable molting. In effect, as Robbin puts it, the insect has eaten its last supper. The Romans used to cover their stable floors with a litter composed mostly of bracken. In one such stable, dating from the first century, 250,000 puparia of the stable fly were found, almost all showing arrested or perverted development. And—as if all this were not enough—bracken also contains a powerful carcinogen, and though cooking destroys most of the bitter tannins and the thiaminase, humans who consume large quantities of bracken fiddleheads over long periods are more apt to develop stomach cancers. With this fearful chemical arsenal, and its aggressively spreading, almost unkillable, deep-underground rhizomes, bracken is potentially a monster, capable of carpeting huge areas of ground and depriving all the other ground-cover plants of sunlight.

Most of the world’s plants—more than 90 percent of the known species—are connected by a vast subterranean network of fungal filaments, in a symbiotic association that goes back to the very origin of land plants, 400 million years ago. These fungal filaments are essential for the plants’ well-being, acting as living conduits for the transmission of water and essential minerals (and perhaps also organic compounds) not only between the plants and fungi but from plant to plant. Without this “fragile gossamer-like net” of fungal filaments, David Wolfe writes in Tales from the Underground, “the towering redwoods, oaks, pines and eucalyptus of our forests would collapse during hard times.” And so too would much of agriculture, for these fungal filaments often provide links between very different species—between legumes and cereals, for instance, or between alders and pines. Thus nitrogen-rich legumes and alders do not merely enrich the soil as they die and decompose, but can directly donate, through the fungal network, a good portion of their nitrogen to nearby plants. United by these multifarious underground channels (and also by the chemicals they secrete in the air to signal sexual readiness or news of predator attack, etc.), plants are not as solitary as one might imagine, but form complex, interactive, mutually supportive communities.

The famous Tule tree, El Gigante, the colossal bald cypress in the churchyard of Santa María del Tule.

Compares the Tule tree with the bristlecones in California, said to be six thousand years old. I mention the famous Dragon Tree of Laguna in the Canary Islands, also reputed to be six thousand years old, a tree which led Humboldt to such lyrical extravagances that Darwin himself was deeply disappointed when, due to a quarantine, he was unable to see it.

As we approach Yagul, Luis points out a cliff face with a huge pictograph painted in white over a red background, an abstract design; and above it, a giant stick figure, a man. It looks remarkably fresh, almost new—who would guess it was a thousand years old? I wonder what the image means: Was it an icon, a religious symbol of some kind? A warning to evil spirits, or invaders, to keep away? A giant road sign, perhaps, to orient travelers on their way to Yagul? Or a pure, for-the-love-of-it pictographic doodle, a prehistoric piece of graffiti?

I am starting to get a sense of a life, a culture, profoundly different from my own. The feelings are similar, in some ways, to those one has in Rome or Athens, but quite different in other ways, because this culture is so different: so completely sun-oriented, sky-oriented, wind- and weather-oriented, as a start. The buildings face outward, life faces outward, whereas in Greece and Rome the focus is inward: the atrium, the inner rooms, the tabernacles, the hearth.

Almost the only green in this parched landscape comes from the bunches of mistletoe tapped into the vascular systems of some of the trees—unwilling hosts (I imagine), for though the mistletoe provides some of its own nourishment through photosynthesis (it is only a “semiparasite,” Robbin tells me), it seems to rob its host of both water and nutrients—the branches distal to them look thin and attenuated. These monstrous bunches of mistletoe make me shudder inside, as I think of them settling on, draining, killing, their host trees. I think of other forms of parasites, and of psychological parasites—and how people can live on, parasitize, and ultimately kill others.

Writing, like this, at a café table, in a sweet outdoor square … this is la dolce vita. It evokes images of Hemingway and Joyce, expatriate writers at tables in Havana and Paris.

The balloon seller, holding her gigantic mass of balloons, crosses the cobbles in front of me to put something in a trash can. Her gait is extraordinarily light, almost floating. Is she, in fact, half-levitated by the helium?

(Theoretical physicists, I once read, lead all scientists in intelligence, with an average IQ in excess of 160.)

B.C., for these people, means Before Cortés, the absolute divide between the pre-Conquest, the pre-Hispanic—and what happened later.

The spring percolates through a whole mountain of limestone before it bubbles out from the side of the mountain into a huge basin, and from here it tracks downward, depositing lime and other minerals as it goes, until it makes its final drop from a semicircle of cliffs. But by this time, with evaporation and absorption, the water is so saturated with minerals that it crystallizes, turns to stone, as it falls—thus the “petrified waterfall.” It is an amazing simulacrum of a waterfall, consisting not of water but of the mineral calcite, yellowish-white, hanging in vast rippling sheets from the cliffs above.

Though the castor bean hails from Africa, they tell us, it is now cultivated in large amounts in Mexico, too, for the oil has innumerable uses: as a lubricant in engines (including the racing oil, Castrol), as a quick-drying oil used in paints and varnishes, as a water-resistant coating for fabrics, a raw material in the production of nylon, a lamp oil, and not least, as a gentle purgative (I am reminded of childhood, and the doses of castor oil I was sometimes forced to swallow). But while the oil is benign, the seed itself is lethal, because it contains ricin, thousands of times more toxic than cobra venom or hydrogen cyanide.

The garbage in the streets, the negligent filth in the hills, Luis says, are moral residues of colonialism, reflecting the people’s sense that the streets, the cities, the lands, are no longer theirs.

Within fifty years of the conquistadors’ arrival, Luis continued, the native population was decimated. Disease, murder, demoralization—entire peoples committed suicide in order to avoid enslavement, regarded death as preferable. Most of those remaining intermarried with the Spaniards, so that almost all Mexicans today are mestizos. But the mestizos were not recognized legally by the colonial governors—they had no rights, and their property could not be inherited by their children, but instead reverted to the state. Life under Spanish rule was becoming intolerable, and revolt, revolution, was becoming inevitable. In 1810 it started, on September 16, the date still celebrated as Mexico’s independence day. The revolution was started, Luis said, by a parish priest, who rang the church bell to rally his villagers, shouting “Long live our Lady of Guadalupe! Death to bad government! Death to the Spaniards!” But it was eleven years before independence was finally achieved in 1821, only to usher in several decades of chaos, under a succession of ineffective rulers, during which time Mexico lost half its territory—Texas, California, Arizona, and New Mexico—to the United States.

“Bread and circuses,” he says, “to distract the masses.” The church here, he feels, is without courage or power. It offers bread and circuses—processions—to pacify the people, but otherwise passively supports a corrupt government.

The walls of the palace are composed of adobe—sticky clay mixed with stalks of corn, animal stools, all fermented together—and conical stones pressed into it, so as to form an elastic base—the stones can move independently in their matrix of adobe, absorbing, dispersing, the force of an earthquake. I am fascinated by this, and draw a diagram in my notebook: the discovery of composites for added strength, for resisting shock, millennia ago. Since nothing so singular can be passed over by the group, a vigorous discussion at once breaks out about composites in nature—the interweaving, at a microscopic level, of two different materials, one crystalline or amorphous, perhaps, and one fibrous, in order to get something harder, tougher, yet more elastic than either component alone. Nature has employed composites in all sorts of biological structures: horses’ hooves, abalone shells, bone, the cell walls of plants. We use the same principle for reinforced concrete, and new synthetic ceramics or reinforced plastics; the Zapotec used it for adobe.

How did the Zapotec cut and shape these stones with such fineness? They had no iron, no bronze, no smelting—only native metals, silver, gold, copper, all too soft to cut stone. But the great Mesoamerican equivalent for metal was volcanic glass, obsidian.

—I am stimulated by the geometric figures around us to speak of neurological form-constants, the geometrical hallucinations of honeycombs, spiderwebs, latticeworks, spirals, or funnels which can appear in starvation, sensory deprivation or intoxications, as well as migraine. Were psilocybin mushrooms used to induce such hallucinations? Or the morning glory seeds common in Oaxaca? People are startled by my sudden loquacity, but intrigued by the notion of universal hallucinatory form-constants, a possible neurological foundation for the geometrical art of so many cultures.

The agave—maguey—is to Central Americans what the palm is to Polynesians. Its very name (our name), agave, means “admirable.”

Distillation was unknown before the Spaniards, and thus there was only pulque, a freshly fermented brew from the maguey (and one which could not be kept, but had to be drunk immediately after fermentation).

(One insect, however, is not to be eaten. One must not swallow a firefly. Swallow three fireflies, it is said, and you’re a goner. They contain a substance with digitalis-like actions, but intensely potent, not to be trifled with.)

The entire village of Matatlán is dedicated to the distilling of mescal, and this sort of specialization is common; this mosaic of specialized villages, this economic organization, is pre-Columbian in origin. Thus everyone in Arrazola carves wood; everyone in Teotitlán del Valle is a weaver, and everyone in San Bartolo Coyotepec, where we have now arrived, makes the black pottery which Oaxaca is justly famous for.

Seeing Don Isaac at work, and his old mother, who cards the wool, and his wife, his brothers and sisters, cousins, nieces and nephews, the half-dozen children in the backyard; seeing them all work—totally engrossed, employed, in different aspects of the business, I have a sense of wistfulness, and of slight disquiet, too. All of them know who they are, have their identities, their places, their destinies, in the world; they are the Vásquezes, the oldest and most distinguished weavers in Teotitlán del Valle, the living embodiments of an ancient and noble tradition. Their lives are predestined, almost programmed, from birth—lives useful and creative, an integral part of the culture about them. They belong. Virtually everyone in Teotitlán del Valle has a deep and detailed knowledge of weaving and dyeing, and all that goes with it—carding, combing the wool, spinning the yarn, raising the insects on their favorite cacti, picking the right indigo plants. A total knowledge is located, embodied in the individuals, the families of this village. No “experts” need to be called in, no external knowledge which is not already in the village. Every aspect of the expertise is located right here. How different this is from our own, more “advanced” culture, where nobody knows how to do or make anything for themselves. A pen, a pencil—how are these made? Could we make one for ourselves, if we had to? I fear for the survival of this village, and the many like it, which have survived for a thousand years or more. Will they disappear in our super-specialized, mass-market world? There is something so sweet and stable about this village of artisans, and its set, fixed place in the culture around it—such villages remain little changed with the passage of time: the sons succeeding their fathers, and in turn succeeded, centuries passing without either development or disruption. A nostalgia for this timelessness, this medieval life, grips me. And yet, I wonder, suppose one of the young Vásquezes were to have great mathematical ability? Or an impulse to write? Or paint, or compose music? Or just a desire to get out, to see the world, do something different—what then? What conflicts would occur, what pressures brought to bear?

When the Spaniards first saw cochineal they were amazed – there existed no dye in the old world of such rich redness and fullness, and so colourfast, so stable, so impervious to change period cochineal, along with gold and silver, became one of the great prizes of new Spain, and weight for weight, indeed, was more precious than gold. It takes 70,000 of the insects, Don Isaac tells us, to produce a pound of dry material. The cochineal insects (only the females are used) are to be found only on certain cacti native to Mexico and Central America – this was why cochineal was unknown to the old world.

This deep magenta or Carmine what’s still not the brilliant color which had captivated the Spaniards, the brave scarlet color that would strike terror into their foes, and that later was used to dye the coats of the Redcoats. Such a bright red only appears when the cochineal is acidified – done here by pouring quarts of lemon juice into it.

Grasshoppers, by a special biblical dispensation, are kosher, unlike most invertebrates. Didn’t John the Baptist live on locusts and wild honey? This always seemed to me a reasonable, even necessary, dispensation, for life in ancient Israel was quite chancy, and locusts, like manna, were a godsend in lean times. And locusts could come in uncountable millions wiping out the always precarious harvests of the time. So it seemed only just, a poetic and nutritional justice, that some of these voracious eaters be eaten themselves. Yet I was outraged, as well as amused, when I visited the Pantanal in Brazil a couple of years ago, to find that the capybaras there, giant aquatic Guinea pigs – sweet, herbivorous animals minding their own business – were at one point almost wiped out because of a special papal dispensation which decreed that, for purposes of Lent, these mammals could be regarded as fish, and thus eaten. Not only a monstrous sophistry but one that drove the gentle capybara almost to extinction. Beavers in North America, Robbin tells me, were also classified as fish for the same reason.

Monte Alban … founded in Olmec times, around 600 BC .. center of Zapotec culture, the political and commercial center of the region, its power extending for 200 kilometers in every direction from the vantage point of its unique mountain plateau. The leveling of a mountain top to create this plateau was in itself an astonishing feat of engineering, to say nothing of providing irrigation, food, and sanitation for a population estimated at more than 40,000.

There was a secular, terrestrial calendar of 365 days and a sacred calendar of 260 days, every day of which had a unique symbolic significance. The two calendars would coincide once every 18,980 days, roughly 52 solar years, marking the end of an era – and this was a time of great terror and despondency, marked by a fear that the sun might never rise again. The final night of the cycle was filled with attempts to avert the dread event by solemn religious ceremonies, penances, and later with the Aztec human sacrifices, and a desperate scouring of the heavens to see which way the stars, the gods, would go.

Christianity, one has the sense, for all its long history, is still in some ways only a thin veneer (in Mexico).

The Maya found that they could cut down the Castilloa elastica tree collect the sticky latex in a trough, and then treat it with the acid juice of morning glory sap. This was particularly convenient since the Castilloa tree was often encircled by morning glory vines. It was only in the 19th century that the further discovery was made by Charles Goodyear that if one treated the crude gum with sulfur and heated it, a highly pliable elastic form of rubber could be made. Goodyear, In this sense, “invented” rubber – except that the same invention had been made by the Maya millennia before. Only very recently was it found that the morning glory contains sulfur compounds which, as in Goodyear’s process, are capable of cross linking the latex polymers and introducing rigid segments into their chains- chains that entangle and interact with one another, producing the elasticity of rubber.

The conquistadors had lusted for silver and gold, and robbed their victims blind to get these – but these were not the real gifts they brought back. The real gifts, unknown to the Europeans before the conquest, were tobacco, potatoes, tomatoes, chocolate, gourds, chilies, peppers, maize, to say nothingof rubber, chewing gum, exotic hallucinogens, and cochineal…

If you don’t know about Fibonacci series, how can you truly appreciate a pine cone?

Gold was not valued by the pre-Columbians as such, as stuff, but only for ways in which it could be used to make objects of beauty. The Spanish found this unintelligible, and in their greed melted down thousands, perhaps millions, of gold artifacts, in order to fill their coffers with the medal. In this sense at least the conquistadors had showed themselves to be far baser, far less civilized, then the culture they overthrew.

How strange that these brilliant and complex cultures, so sophisticated in mathematics and astronomy, in engineering and architecture, so rich in art and culture, so profound in their cosmological understanding and ritual – were still in a pre wheel, pre compass, pre alphabet, pre iron age. How could they be so “advanced” in some ways, so “primitive” in others? Or were such terms completely inapplicable? if we compare mesoamerica to Rome and Athens, I was beginning to realize, or to Babylon and Egypt, or to China and India, we find the disjuncture bewildering. But there is no scale, no linearity, in such matters. How can one evaluate a society, a culture? We can only ask whether there were the relationships and activities, the practices and skills, the beliefs and goals, the ideas and dreams, that make for a fully human life.

This has turned out to be a visit to a very other culture and place, a visit, in a profound sense, to another time. I had imagined, ignorantly, that civilization started in the Middle East. But I have learned that the new world, equally, was a cradle of civilization. The power and grandeur of what I have seen has shocked me and altered my view of what it means to be human. Monte Alban, above all, has overturned a lifetime of presuppositions, shown me possibilities I never dreamed of. I will read Bernal Diaz and Prescott’s 1843 Conquest of Mexico again, but with a different perspective, now that I have seen some of it myself. I will brood on the experience, I will read more, and I will surely come again.

There is nothing to do but sit under the great bald cypresses by the river and enjoy the simple animal pleasure of being alive (perhaps the vegetable pleasure too; feeling what it might be like to live, unhurried, century after century, and still feel youthful at 1000 years old.)