Paul Theroux is one of my two favorite travel writers along with Pico Iyer. I have read all his nonfiction books. I read this book when it first came out (it’s a Mexican journey but focuses quite a bit on the South of Mexico) and felt compelled to revisit it after reading The Oaxaca Journal by Oliver Sacks. While Sacks is humble, Theroux is NOT! But both of them weave a great story!

The Labyrinth of Solitude, Octavio Paz’s reflections on death and loneliness, masks and history, is pitiless but also one of the most insightful books I have read on Mexican attitudes and beliefs.

But no sooner had I gotten behind the wheel than a feeling came over me that was like being caressed by a cosmic wind, reminding me of what travel at its best can do: I was set free.

Don’t go thar! You’ll dah!”

Another lesson: it’s a mistake to disclose that you’re passionate about going anywhere, because everyone will give you ten reasons for not going—they want you to stay home and eat meatloaf and play with a computer, which is what they’re doing.

“Be careful,” a platitudinous formula all travelers hear when they set out—words that often sound to me empty, resentful, and envious, the sort of precaution that licenses the sullen stay-at-home slug to gloat at some point much later, “See, I told you so!”

“The machete is the most convincing form of argument.”

Mexico is “the deadliest country for journalists, edging out Iraq and Syria.”

The migrants make no sound.

“We go to California all the time,” he said. “We buy jeans, shirts, TV sets. A lot of it is made in Mexico. Even with the Mexican duty we have to pay on the way back, it’s cheaper for us.”

And like most of the Mexican border towns I was to visit, Tijuana was thick with pharmacies, dentists, doctors, and cut-price optometrists.

“Solo mirando,” I said at each place. Just looking, the theme of my traveling life.

To regulate the flow of fieldworkers, the Bracero Program (Mexicans working on short-term contracts) was established in 1942 under an agreement between the US and Mexico. The American need for cheap labor has defined the border culture.

It is at once more heartening and more hopeless than I had imagined. Nothing fully prepares you for the strangeness of the border experience.

Renting or buying a house on the US side is prohibitive for many, so a whole cross-border culture has developed in which American citizens of Mexican descent live in a house or an apartment—or a simple shack—in a Mexican border city, such as Juárez or Nuevo Laredo, and commute to work in El Paso or Laredo.

The notion of building a wall strikes most people on either side as laughable. The belief is: show me a thirty-foot wall, and I will show you a thirty-five-foot ladder.The Tohono O’odham Nation, half in the US, half in Mexico, divided by the border, resists with its slogan, “There is no O’odham word for wall.”

“I guess Canal Street could now be called Root Canal Street,”

How to know another country—stay longer, travel deeper.

It was Mark’s contention that Mexican immigration is “net zero,” neither a surplus nor a deficit—a wash. The growth now was from Central America, thousands of people fleeing violence. And what the US authorities call Special Interest Aliens—Africans, Indians, Pakistanis—who crowd the detention cells up and down the border.

Luiselli writes that so many of the women and girls who get to the border are raped on the way (she says 80 percent of them are sexually assaulted), they begin taking contraceptive pills before they set out.

And you could probably say the same about the large number of British writers, Irish musicians, Nigerian novelists, Indian techies, French intellectuals, Russian hockey players, and Brazilian surfers who come to the States—like the despised Mexican—for the space and spontaneity of a convenient and roomy country, and an opportunity to enrich themselves.

“The level of sadism [in Mexico] is overwhelming, and it is largely a reflection of the impunity in the country.”

The cartels battling each other and the Mexican military battling the cartels.

The Gulf cartel, the Sinaloa cartel (El Chapo in charge), and the Zetas had been in a three-way struggle for domination—the Mexican army and police fighting all three, and sometimes joining them.

A poster of Santa Muerte, Holy Death, a skeleton in a hooded cloak, with a grinning skull, her bony hand wrapped around the shaft of a scythe. The saint of desperate people, and of criminals and drug traffickers and whores; the saint who offers hope and does not blame or ask for repentance. All that Santa Muerte asks is veneration.

I ended my traverse from Tijuana with the vision of the border as the front line of a battleground—our tall fences, their long tunnels. We want drugs, we depend on cheap labor, and, knowing our weaknesses, the cartels fight to own the border.

And I thought: the odd, medieval strategies of the very poor, clowning, performing, selling homemade food; but not begging.

I was now deeper into Mexico than I had driven so far.

Experience of living under a corrupt government and trying to stay honest yourself made people cynical and distrustful of authority, but at the same time self-sufficient and dependent on friends and family, because no one else would help you.

“The Chinese do that—drink hot water,” I said. “They call it white tea.”

San Luis Potosí is a victim of the usual Mexican pattern of the old harmonious colonial city brutally martyred in the cause of modernization—officialdom

“The past of a place survives in its poor.”

Good manners also persist in societies so poor they are ignored and uncorrupted by hustlers and money people, as politeness is a habit of life, a way of getting on.

“The most beautiful manners I have met with are in countries where men carry knives, and if anybody gives them a nasty word or a nasty look, stick them into him.”

You don’t need to be in Mexico long to understand that it is a country of obstacles, a culture of inconvenience.

Why would a young mother of small children—like many I met on the border—take the risks of hopping the fence and enduring the privations of hiking in the desert just to labor for minimum wage in (as some told me) a meatpacking plant or a hotel? One obvious answer is that the risks and privations in Mexico are much worse that those endured in a border crossing.

What I had learned on the border from the mothers intending to cross was not that they wished to make a new life in the States, but that they hoped, as a solution, to make enough money to keep their family together in Mexico.

The African masks at the Trocadero Museum of Ethnology in Paris caught the eye of young Pablo Picasso: “A smell of mold and neglect caught me by the throat. I was so depressed that I would have chosen to leave immediately,” he said. “But I forced myself to stay, to examine these masks, all these objects that people had created with a sacred, magical purpose, to serve as intermediaries between them and the unknown, hostile forces surrounding them, attempting in that way to overcome their fears by giving them color and form. And then I understood what painting really meant. It’s not an esthetic process; it’s a form of magic that interposes itself between us and the hostile universe, a means of seizing power by imposing a form on our terrors as well as on our desires. The day I understood that, I had found my path.”

The bat was known in Zapotec as bigidiri zinnia—flesh butterfly (mariposa de carne).

The idle curiosity that is available to any person with a car in Mexico and no particular place to go.

Saint Jude is the second-most-popular saint in Mexico. The most venerated one is Our Lady of Guadalupe (But both of these saints have heavy competition in popularity from Santa Muerte, the robed skeleton whose bony image and lipless grin is everywhere.)

Being in San Miguel like being trapped in a cyclorama of colonial cuteness.

San Miguel de Allende by most accounts is one of the most desirable retirement destinations in the world.

For 1,000 pesos, or $50, a week, you could hire a maid to work an eight-hour day (Sundays free), cleaning and making simple meals. Perhaps double that if she lived in. A night nurse would be about $25 a week. Gardeners and menials were paid a pittance.

It is pleasant in Mexico to sit by the beach, inert and sunlit, sipping a mojito, but who wants to hear about that?

The accepted way to broach the subject of a bribe in Mexico is to say, “How can we resolve this?”

I was fascinated but anxious, because this crooked cop was someone to fear, the embodiment of what all Mexicans fear: corrupt authority. The historian and anthropologist Claudio Lomnitz has written that the Mexican state exists on bribery and coercion. In a brisk, persuasive essay Lomnitz suggested three causes for this crisis of corruption. The state was weakened and bankrupted in the nineteenth century by fighting small, costly wars with Spain, France, the United States, and with its own indigenous peoples. Mexico’s financial instability carried over into the twentieth century and beyond the Revolution of 1910. So how is the country sustained? By informal trade—folks working outside the law—that dominates as much as two-thirds of the Mexican economy, and its improvisational infrastructure. This involves minor infractions, on the whole, millions of them. “But informal economies can only be regulated with petty corruption—by police who are bribed to look the other way.” This corruption has become systemic, a way of doing business. Cops make money by shaking down anyone they can. The narrow tax base is the second cause of corruption. Mexico, like Saudi Arabia, essentially a petrocracy, survives because 30 percent of its tax revenue comes from one reliable source—Pemex, the national oil industry. Most people don’t pay tax, either because they are too poor or because they exist outside the system. “Such a narrow tax base fosters low levels of accountability.” “Mexico’s quagmire of impunity has also been affected by the American drug and gun control policies.” The border is historically lopsided, Lomnitz writes, describing the third reason. The US has criminalized the economy that services its vast appetite for drugs. This means that because Mexican law enforcement is weak and corrupt, “the temptation to outsource illegal activities is natural—even perfectly predictable.” Border traffic is stimulated, too, because guns are banned in Mexico but sold freely in the States. The consequence is that Mexico pays “a disproportionate share of the cost of the American gun and drug habits,” further weakening the state and creating paradoxes that are clearly apparent on the border. For example, in the year Ciudad Juárez had a higher murder rate than Baghdad, El Paso, just across the river, was ranked as the second-safest city in the US. “But where did Juárez’s drug gangs purchase their guns? El Paso. And where did the drugs that moved through Juárez end up? El Paso.”

“You must be careful, Don Pablo,” Rudi Roth said at his hotel. “Mexico is surrealistic.” Gabriel García Márquez, who had lived not far from Rudi’s hotel, called Mexico City “Luciferian” and “as ugly a city as Bangkok.” Leonora Carrington, an English expat, writer, and surrealist painter, whose studio was four streets south in this Roma district, on Calle Chihuahua, once said, “I felt at home in Mexico, but as one does in a familiar swimming pool that has sharks in it.”

But in a poor country, people value what little they have: their dignity, their lives, their children most of all—and their long memories. Their memories are merciless.

About those police: they are not the protectors they seem.Almost the entire police force is comprised of narcos in police uniforms, using police weapons and squad cars.

“In Mexico, police and military at every level have fully merged with forces of organized crime,”

Mexicans spend very little time railing against the US government, because in their experience, government by its very nature is corrupt, often criminal, and the poor are its victims.

Perhaps these kids felt it was their turn to exact revenge on those who seemed even more like outsiders than themselves.

‘The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there,’

The notion of ranging widely in a big country attracted me

“For Mexico to make this house a museum would be like the people of Hiroshima creating a monument for the man who dropped the atomic bomb.”

And I thought: I am content. I have achieved that elusive objective in travel—a destination. I have arrived. I am happy, one of the hardest moods to describe.

Coger is “to take” in Spain, but “to fuck” in Mexico.

I could not formulate this for Rosi, but I felt that for art, for writing, for anything creative to have value, it must be passionate and personal.

Frida as a mutilated, mustached, and unibrowed madonna was perhaps more admired in Europe and the United States than in Mexico itself.

Identity, misunderstanding, risk, solitude, confusion, often in the long shadow of the United States.

The satisfactions and inconveniences of being Mexican.

People only gain recognition in Mexico when they make a successful career for themselves abroad.

It’s true of writers in many other countries, who, for self-esteem as well as to make a living, need the authority of foreign approval.

“The northern border is a wound that pains all Mexicans.” As for the indignity of the interrogation, “Every human being should experience it at least once, so as to know what others go through.”

At its best, teaching is also an experience of learning from your students.

The Santa Muerte cult, in its florid, more macabre form, is more recent, and the present day has seen a great resurgence of followers, especially among criminals.

“La Santa Trinca,” Julieta read as she gazed at a portrait of Mexico’s holy trinity, Saint Jude, Jesús Malverde, and Santa Muerte—bearded apostle, bandit, and skeleton.

It seemed to me that death worship was not the point here. Santa Muerte was not the image of someone who was once living, but rather a representation of death, and her most appealing aspect was that she turned no one away, certainly not sinners, whom she welcomed, forgiving everyone, especially the wickedest among us.

As time went on, I fribbled the days away as a flaneur, became lazy and presumptuous in the manner of a city dweller, and developed the big-city vices of procrastination, eating late, sleeping longer, yakking in cafés, and pretending to be busy.

It was easy to see how so many foreigners visiting Mexico City decided to spend the rest of their lives here, while dishonestly complaining it was a shark tank or Luciferian.

The criminalizing of humanitarian acts on the border made every American complicit in persecuting migrants.

It was easy to imagine a boy or girl in their late teens, armed with a Glock and a stun gun, in a green Border Patrol uniform and a Stetson hat—such an armed teenager representing the federal government—facing a defiant activist or a cowering migrant. The ensuing confrontation would not be a meeting of minds.

The trip reminded me that most headlong hallucinatory brain-bending drug episodes (at least in my life) begin with the mildest, most prosaic tinkering and hoo-ha. At first there is only mild discomfort, a pukesome catch in the throat, and then, in an eruption of phosphenes, blinding light in the lantern of your head, as the body surrenders to a narrowing liquefaction, and finally a transformation, as one is borne along a river of lava, or it might be marmalade, with a chorus of warping chirrups, perhaps of demented sparrows or speeding schools of translucent reef fish—only the synapses know. At the start is the decapitation, and you melt, you vanish, and in a welcome dawn you are reborn as plasma, until reincarnated as damp flesh, blinking and wondering, What just happened? The bus was like that, but it took a while. Travel can mimic such an episode, which is why they are both called trips.

Mexican authority figures are meaner, darker, better fed, and more muscled than the average Mexican, heavily armed and unsmiling.

“Looking for drugs?” I asked my new friend Bonifacio. “No. The drugs go the other way. They are looking for guns and money.”

The moan of the engine and slow gear changes, a sound like grieving.

The bounce and swerve of the bus rocked me like a dissolving drug.

“The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved.”

“Nobody knows what’s going to happen to anybody, besides the forlorn rags of growing old,”

There are two Mazatláns. One is the centro histórico, with its market and churches and the Teatro Ángela Peralta—built in 1874, for opera, boxing, movies, and plays; restored in 1992 as a venue for local musicians and dramatists and dancers—its old plazas and small bistros, hospitable to locals. The other, flashier, golden Mazatlán, the Zona Dorada, six miles up the beach, at the top end of town, with its grand hotels and resorts, is dismissed by locals as the destination of rich gringos, and financed to launder drug money, as a man told me with a dismissive laugh: “Dinero lavar!”

“If you didn’t want drugs in your country, we wouldn’t have cartels in ours.”

“Yes, we have El Chapo Guzmán, but you had Al Capone!”

it was compelling and comforting in Old Mazatlán, an ageless scruffiness, a sense of vitality in decay, an argument against luxury, boutique hotels, and pestering waiters in tailcoats. The pleasure of relaxing on a worn sofa.

Belief gains strength in the absence of facts.

And I was overcome with sadness, the melancholy of the voyeuristic traveler, and thought: This is what happens when you stay too long in a place. You begin to understand how trapped people feel, how hopeless and beneath notice, how nothing will change for them, while you the traveler simply skip away.

Mexicans still know how to fix things: the body shops of Tijuana smooth the dented cars from California.

I was to find, as I had on the border, that no matter how dreary-looking a Mexican city or town, it nearly always has a good place to eat, which is worth stopping to find. In the absence of any other comfort, suffering poor housing, violent streets, bad government, and wicked cops, Mexicans defend their food and take pride in its regional differences—in many cases, define themselves and their towns in the uniqueness of their food.

I discovered that one way to understand a culture was to spend a longish holiday in the company of a single nationality.

I saw that a Mexican heaven, a Mexican holiday, is an all-you-can-eat buffet. They were not drinkers, but they were eaters. A Mexican middle-class vacation meant unlimited access to the buffet and a place for the kids to play and for the grandparents to snooze. No one used the tennis courts, no one was reading.

But no sunny moment in Mexico is without a cloud.

People were hoeing, their backs bent, clawing at the soil, the iconic postures of peasants.

Because this is in Mundo Mexico, on the plain of snakes, its citizens are overlooked by the government, its workers exploited and underpaid, its teachers belittled, nearly all its city dwellers living in small spaces. But the people are making the best of it, because it was my experience that Mexicans might be mockers and teasers, but they are not idle complainers.

When an oppressed group in Mexico airs a grievance, it doesn’t mumble. It takes to the streets with resolve, holds a demonstration in the main plaza, camps out in front of a ministry in a defiant vigil, burns a bus, blocks a motorway, or, in the case of the Zapatistas in Chiapas, arrives on horseback out of the jungle and declares an insurrection, taking over an entire state and eventually running it so well that the government (out of shame or indifference or confusion) turns its back on the rebels, pretends they don’t exist, and allows them to create a better way of life.

A museumgoer when I have nothing better to do, I avoid writing much about collections, because a visitor should enter a museum innocent of what’s to come, be allowed to make discoveries, and not be nagged into seeing specific works.

in Mexico, political action such as a roadblock or a protest is also a social occasion.

In places the ruts were a foot deep and very wide, some of them filled with water where goats were drinking.

Mixteca, came from a Nahuatl word, mixtla, meaning cloudy land.

Cooperation and mutual aid were keys to the survival of their Mixteca culture.

It emerged in the Yanhuitlán Inquisition that the stubborn Mixtec adherents offered food and incense to the gods at their home altars before going to church, “so as to avoid the wrath of their ancestors.” And in another devious stratagem, uncovered by the inquisitor, they chewed a narcotic green tobacco (Nicotiana rustica) they knew as piciete, to become thoroughly stoned during Mass, so blissed out on the weed that they would not hear the alien preaching.

“It’s a strange and insufferable uncertainty to know that monumental beauty always supposes servitude,” Albert Camus wrote in the last volume of his Notebooks (1951–1959), speaking of the forced labor that creates great buildings like this. (He was in Rome when this idea came to him.) “Perhaps it’s for this that I put the beauty of a landscape above all else—it’s not paid for by any injustice and my heart is free there.”

Poor but complex and handsome, like so many of its people, and dignified in its poverty, indestructible in its simplicity, Oaxaca was a proud place, too.

I was reminded again of how “the past of a place survives in its poor”—how the poor tend to keep their cultural identity intact.

The rich tend to rid themselves of their old traditions, except in a showy or ritualized way, because they became wealthy by resisting them and breaking rules.

The Mexican republic comprises thirty-one states. The north of the country lies in America’s cruel, teasing, overwhelming shadow—a shadow that contains factory towns, industrial areas, smuggler enclaves, and drug routes. Mexico City, in the middle of the country, is like an entire nation, of twenty-three million people—much larger than any Central American republic. But the south of Mexico, the poorest region, is a place apart, rooted in the distant past, some of its people so innocent of Spanish, they still speak the language of the 2,500-year-old civilization of Monte Albán, a few miles outside Oaxaca, enumerating the beautiful temples by counting all ten of them in Zapotec on their fingers: “Tuvi, tiop, choon, tap, gaiy, xhoop, gats, xhon, ga, tse.”

Oaxaca is remarkable for having resisted modernization—a great impulse for any venerable city—and for valuing its cultural heritage. Because traffic is slowed to a crawl by the narrow streets, most people walk. A city of pedestrians moves at a human pace in most other respects, too, and is inevitably a place where small details are more visible, and noticed and appreciated. Strollers see more, and are more polite, than drivers.

That most of these street vendors are Indians—Zapotec and Mixtec—deepens the town’s cultural authority: five hundred years after the conquest—Oaxaca was founded in 1529—the same indigenous people persist, tenacious and undiluted, still speaking their ancient languages, easily recognizable as Mexico’s native aristocrats, their same hawk-nosed profiles chip-carved on the murals disinterred from the ruins at Monte Albán and Mitla, not far away. As Benito Juárez (raised speaking Zapotec) described his own family, they are “Indios de la raza primitiva del país”—that is, Indians of the original race of the country.

Because of the wide doorways that line the sidewalk, and the open doors, Oaxaca’s streets are filled with the fragrance of its characteristic cooking.

The antagonistic graffiti, violating the facades and soaked into the old stonework: HOY BARRICADAS, MAñANA LUCHA. Today barricades, tomorrow the struggle. And: SE ALISTAN LAS BOMBAS, SE AFILA EL PUñAL. The bombs are readied, the dagger is sharpened. And: ZAPATA VIVE!

I realized that first morning how, in studying a language, being asked and answering direct questions, you reveal yourself; how so much of such a class is revelatory—sometimes simple, often confessional.

Making a living this way, my own way, self-employed—that was something to like. Curious to know more about Mexico, I could get in my car and drive from home to the border, and from the border to Mexico City, and then here, making notes at the end of the day, answerable to no one.

“El acto de la creación” What I like most about my work is the act of creation.

And there was the Mexican expression for being tactless or off-base or blundering: mear fuera de olla—to piss outside the jar.

“The northerners say that southerners are lazy and short,” Herman said in Spanish. “Southerners say northerners are tall and work too much.

“Death comes to all and makes a mockery of us all.”

Muriel Spark, in her novel Memento Mori: “If I had my life over again I should form the habit of nightly composing myself to thoughts of death. I would practice, as it were, the remembrance of death. There is no other practice which so intensifies life. Death, when it approaches, ought not to take one by surprise. It should be part of the full expectancy of life. Without an ever-present sense of death life is insipid.”

“What do I miss? Food and friends. The diversity of culture”

In the States you have poor people, but generally they’re the ones who don’t want to work. Here we have poor people, but poor because they have no opportunities. It’s sad.

“Then comes Sunday morning, with the peculiar looseness of its sunshine.”

“These writers show a total lack of curiosity or understanding beyond the most superficial perception of the place and people.”

“To buy and to sell, but above all to commingle.”

Tlacolula Market – These enterprising market men and women are among the poorest in Mexico, the ones who hanker to go to the US because they are hard-up, and who hanker to come home, because a market like this exists nowhere else.

D. H. Lawrence makes a point of talking at length about malodorous sandals, having heard that an essential ingredient in the tanning of Mexican leather is human excrement, a traditional practice still used in parts of the country.

Teasing, especially the public sort, as well as the joshing in a joking relationship, always contains an element of hostility.

And we drank, the first sip a knife blade of liquid slipping down my throat and stinging my eyes, the second sip soothing the laceration of the first sip. The third sip induced a feeling of well-being, warming my face. The second cup percolated to my extremities, a relaxation of fingers and toes, a mollifying of the mind and spirit.

I’m home. Less pressure.

My delirium, part mezcal, part pure traveler’s bliss.

Mexican mourning, a process of easing the spirit of the dead person into the next world.

This drew a snort of disapproval from an old woman. “No,” she said. “In the past we greeted each other four times a day—four greetings. We kissed hands.” “Like this,” Sarahi García said, and demonstrated how a person would extend both hands, turned down, offering them to be kissed. “Yes,” the old woman said. “But these days the young people just say ‘Hi!’”

The courtliness of Mexican manners,” I said, thinking of how he had written: “I have heard a half-naked laborer bent double under a sack of coffee-berries murmur, ‘With your permission,’ as he passed in front of a bricklayer who was repairing a wall.”

Each thing mattered, each person was essential. Even the dog mattered, as the proverb had it: Where there is veneration, even a dog’s tooth emits light. It was something I needed to know.

It was a reminder that in its essence, travel is less about landscapes than about people—not power brokers but pedestrians, in the long march of Everyman.

Santa María Ixcatlán, so poor that real money seldom changed hands there.

A slanted landscape of leaning creatures and buildings.

A family of five in the village lived on an average of 700 pesos a month, about $37, which was, as I learned later, much less than a family of the same size in rural Kenya. The average monthly income for Mexico was ten times that, but this rural area was at the periphery of the economy, the poorest people in the country.

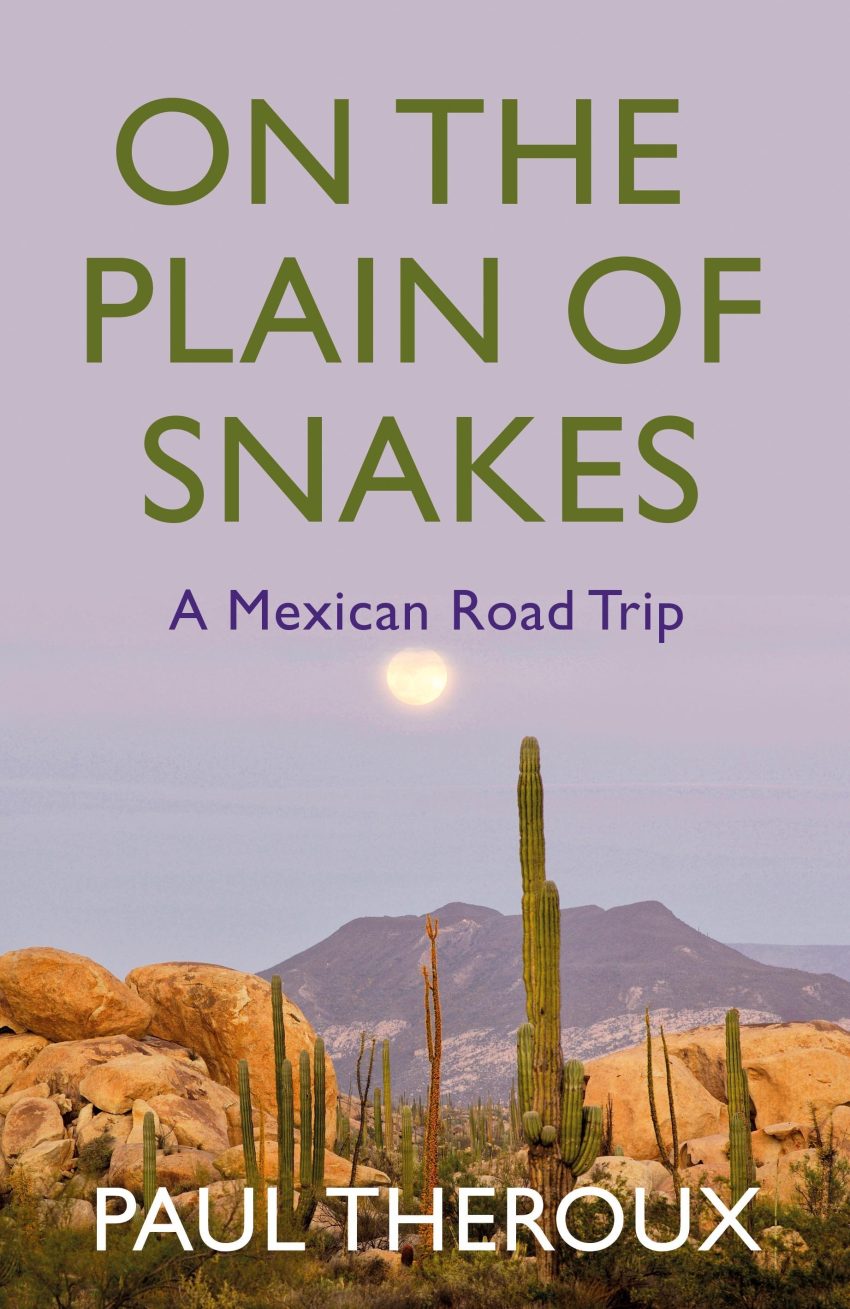

“What is the meaning of ‘Coixtlahuaca’?” “El llano de los serpientes.” The plain of snakes.

When Mexican writers are asked to name an important Mexican novel of the past sixty years or so, they usually suggest Pedro Páramo (1955) by Juan Rulfo,

“The Mexican . . . is familiar with death, jokes about it, caresses it, sleeps with it, celebrates it; it is one of his favorite toys and his most steadfast love,”

Octavio Paz writes in The Labyrinth of Solitude, with his customary hyperbole. ‘If they are going to kill me tomorrow, let them kill me right away.’”

Paz says “death,” not “dying.” Dying is another matter altogether, something to be avoided because it implies pain—an anguished, agonizing process, sometimes lengthy, not a sudden bitter end, but an often prolonged terminal condition. Yet death as a certainty and a promise is the eternal Mexican specter at the feast. Paz is Mexican in his commitment to pessimism.

Magical realism, once gushed over, now seeming somewhat dated and pretentious, was perhaps a third-world reaction to the horrific and hard to bear in daily life, a willful turning away from reality, a flight into banal bedazzlement, as Salman Rushdie, who has made his reputation producing it, described, in Imaginary Homelands: “‘El realismo magical,’ magic realism, at least as practiced by Márquez, is a development out of Surrealism that expresses a genuinely ‘Third World’ consciousness. It deals with what Naipaul has called ‘half-made’ societies, in which the impossibly old struggles against the appallingly new, in which public corruptions and private anguishes are somehow more garish and extreme than they ever get in the so-called ‘North,’ where centuries of wealth and power have formed thick layers over the surface of what’s really going on.” This oral tradition of the supernatural has been appropriated by others for fiction. But the term “magical realism” is an academic justification—that is, a pompous way of avoiding the term “fantasy.” It is a literature of denial, a literature of hokum, a form of extravagant literary nostalgia for an earlier, animistic era, a culture of masks, sacrifices, apparitions, and fairy tales. It is my friend Salman Rushdie and other literary refugees shrinking from the horrors of India to sit in New York or London and serve up flapdoodle and farce and comic tales of bedazzlement about a prettified peasantry, while half a billion Indians living in poverty on the subcontinent struggle to find their next meal. I admit the wisdom and vitality of García Márquez’s novels and short stories, and the power of his imagination, his avoidance of whimsy, his great comic gift. He is the best of this bunch, writing about the hard-up hinterland, yet even his work seems a brilliant confection, fable and allegory not being to my taste. “It’s like farting ‘Annie Laurie’ through a keyhole,” Gulley Jimson says. “It may be clever but is it worth the trouble?” I have spent my reading and writing life, and my traveling, trying to see things as they are—not magical at all, but desperate and woeful, illuminated by flashes of hope.

The regional novelist or short story writer—Mexican versions of the rusticated Chekhov, the Wessex-dwelling Thomas Hardy, the gentleman farmer William Faulkner—hardly exists in Mexico.

A village is where you’re reminded you are poor, where you starve and die; it is a place to flee. (“Take me with you—take me away from here,” an old woman said to me later in my trip in a village in the Isthmus. “I don’t care where you come from. I want to go there.”)

“Someday one has to leave.”

One of the servants, Felix, stops the clock every night in the grand house so that the family can exist outside time: “After dinner, when Felix stopped the clock, he let his unlived memory run freely. The calendar also imprisoned him in anecdotic time and deprived him of the other time that lived within him.”

Esquivel has a heightened intensity of observation that seems to me a gift of Mexican women writers, perhaps because as women and nurturers they are forced so often to wait, studying their condition, being patient, existing in suspense. But that patience provokes in them an active inner life and intense emotion; it is a patience that men lack, demanding that you see, rather than persuading you, as Esquivel does, with detail.

Once a Mexican intellectual has done violence to another Mexican intellectual, nothing remains of the carnage to anatomize. They are like cartel assassins in this respect.

But it is easy in Mexico to leave the main road, take a side road, turn into a narrow track, and wind up in the past, and the past often seems like an underworld.

“No danger, sir. Because no one ever caught the snake, and as a result they never had good luck.”

“I crossed the border. Everyone was kind. My bosses were good to me. The thing I missed most was eating with my family. It’s very lonely in the United States. So I came home.”

That sometimes happened. A person went across, spent years in the States, then returned presumido (stuck-up).

“You should go. It’s amazing,” Nilo said, talking over the man. “It’s like being a goat in a green valley! You see it and you want to eat it all! You drink and eat and spend money!”

“Tejate,” Isaac said. “It tastes good.” The liquid poured into the bowls was gray, with a grainy texture and a scum of bubbles on the surface, and it tasted sweetish, a thick soup of—so they explained—maize, flor de cacao, peanuts, coconut, and roasted mamey seeds, or pixtle in Zapotec. Because of the extensive grinding, kneading, roasting, and toasting of ingredients, this pre-Hispanic concoction is called one of the most labor-intensive drinks on earth.

“Social well-being” became a Mexican euphemism for oppression or targeted assassination.

No one is more cautious or more prompt with warnings than the Mexican away from the security of his pueblo.

“Isn’t collecting turtle eggs illegal?” “Nothing is illegal here,” Francisco said with a crooked smile.

Tureens held spiced and cooked goat heads, staring with sightless eyes, defying you to eat them.

They were muxes—“mooshes”—for which Juchitán is famed, men who dressed as women but were physically male.

And I wondered, as you wonder over fish in Mexico: Am I being poisoned?

It is a truism that Mexican travel usually involves a spell of gut sickness, known in Mexican slang as chorro, a splash.

“There’s a huge difference between being muxe and gay. Gays have a tough time in Mexican life. They call us mayate. What is mayate—dung beetle? It’s also slang for a black person.”

Zapotec society is essentially matriarchal.

The main church in Juchitán is the Parroquia de San Vicente Ferrer. One of the traditions here is that God gave Saint Ferrer a bag of muxes to scatter throughout Mexico. But when the saint arrived in Juchitán, the bag fell apart and all the muxes ended up in this one place.

Mexico is rich in many tourist-friendly respects—the traditional hospitality, the varieties of food, the elaborate fiestas, the gusto of the language, the consolations of family and faith.

The way forward in any relationship was based on trust, but trust was not taken for granted. It was something you had to earn.

Ganar el respeto—to win respect—was a Mexican imperative; more profound was ganar la confianza, to win trust.

Silence, exile, and cunning (James Joyce’s words of defense) are useful strategies to any wanderer, especially one who wishes to write.

‘Cancún,’ in Maya, means Nest of Serpents.”

“Although our foundational myth, and our coat of arms, suggests that snakes are forces of evil that must be devoured by the virtuous eagles, the truth is more complicated than that. The eagles soar in the sky alone, but we Mexicans share the land with snakes.”

Another example of the Mexican government strategy of inaction, the political theory of doing nothing, on the assumption that humans have a habit of forgetting—a perverse assumption, since Mexico seemed to me a nation torn by total recall.

The interior of the basilica of San Juan Bautista was ablaze with flames. Worshipers crouched on the floor arranging candles, fifty or a hundred in symmetrical patterns, then lighting them and, in the candlelight, drinking Coca-Cola and ritually burping—eructation believed to be salutary—and splashing libations of Coke on the church floor, which was covered with sand.

if the chosen saint did not grant the supplicant’s wish, the deity could be punished, just as the Zapotecs and Mayans punished their gods and saints, lashing their images with whips.

The land belongs to those who work it with their hands.

“The movements which work revolutions in the world are born out of the dreams and visions in a peasant’s heart on a hillside,”

“For them the earth is not an exploitable ground but the living mother.”

One central Tzotzil tenet affirmed harmony with the natural world, asserting that trees and bushes have souls, and every human has two souls. One soul is in the body and the other resides elsewhere, in an animal—a possum, a monkey, a jaguar, a bat (“Tzotzil” comes from the Mayan word for bat)—the power animal and protective creature, a spirit companion. In the peaceable kingdom of Lacandona, Tzotzils could not harm an animal without harming themselves.

After today, the people who are the color of the earth will never again be forgotten.

NAFTA was regarded by the Zapatistas (and many others) as exploitative, and disastrous for small farmers all over Mexico.

“Of all the people in Mexico, the Indians are the most forgotten.”

“It’s about being anonymous, not because we fear for ourselves but rather so they cannot corrupt us.” He also said, “We are the Zapatistas, the smallest of the small, those who cover their faces to be seen, the dead that die to live.”

“The world’s new masters have no need to govern directly. National governments take on the role of running things on their behalf. This is what the new order means—unification of the world into one single market.

The unification produced by neoliberalism is economic: in the giant planetary hypermarket it is only commodities that circulate freely, not people.”

“The power we get through words . . . to write so that death doesn’t have the last word.”

“The men who excite adoration, who are what is called natural leaders (which means really that people feel an unnatural readiness to follow them), are usually empty. Human beings need hollow containers in which they can place their fantasies and admire them, just as they need flower vases if they are to decorate their homes with flowers.”

I dream like a genius!

Although Alejandro was ably translating, I was distracted by the Comandante’s proscription about not wanting to be merely an anecdote, because it is in the nature of travel to collect and value telling anecdotes. Yet this experience was something else, a clarification of much that I had seen in my traveling life, an elaboration of the challenges of poverty and development, the curse of bad government and predatory corporations, the struggle of people living on the plain of snakes who wish to choose their own destiny.

I felt this widely read man must have known in his old age the lines of T. S. Eliot in “East Coker” (“Old men ought to be explorers”) or the epiphany Czesław Miłosz had described in “Late Ripeness”: Not soon, as late as the approach of my ninetieth year I felt a door opening in me and I entered the clarity of early morning.

One of the greatest thrills in travel is to know the satisfaction of arrival, and to find oneself among friends.

“I’m going to miss San Cristóbal,” a man says in Charles Portis’s Gringos. “This place is cool and pleasant the year round, a fat man’s dream.”

The history of Chiapas is a litany of invasion, massacre, punitive missions, and extermination, at last defended and redeemed by the Zapatistas.

“I can clean your house. I can look after you. Take me with you—take me away from here. I don’t care where you come from. I want to go there.”

A feeling of melancholy descended on me. I guessed this was because of the self I remembered from being here long before, the dejected man who had no idea where he was going. But I was a different person now, because I knew where I had been.

Yes, I was lucky—incredibly so. Lucky in the people I met, lucky in the friends I made, lucky even in my mishaps, my always emerging unharmed, with a tale to tell. More than fifty years of this, ever the fortunate traveler.